Arctic by RIB - Episode 13 Toward the Northwest Passage

DAY 33rd – Thursday, 4 of August

Position: 77°28΄N 69°14΄W – Qaanaaq (Thule)

We were moored to the edge of the long jetty which stretches for about 100 meters perpendicular to the sandy beach of the village of Qaanaaq. Here there is no true port and the jetty had just been built. When the water recedes with the tide the depths are so shallow that only the small boats of the locals can float there.

Fortunately for us, there was one point where the depth reached our draft with the motors down, 80 cm (31.5”) and so we were able to tie up without any problems. Otherwise we would have to stay anchored out and go to the beach with our tender for resupply or for any other reason.

Special care is needed when approaching the beach while the waters are high here. We had to stay several meters outside at the end of the jetty because when the waters receded, the depths were only a few centimeters and many rocks started becoming visible above the surface.

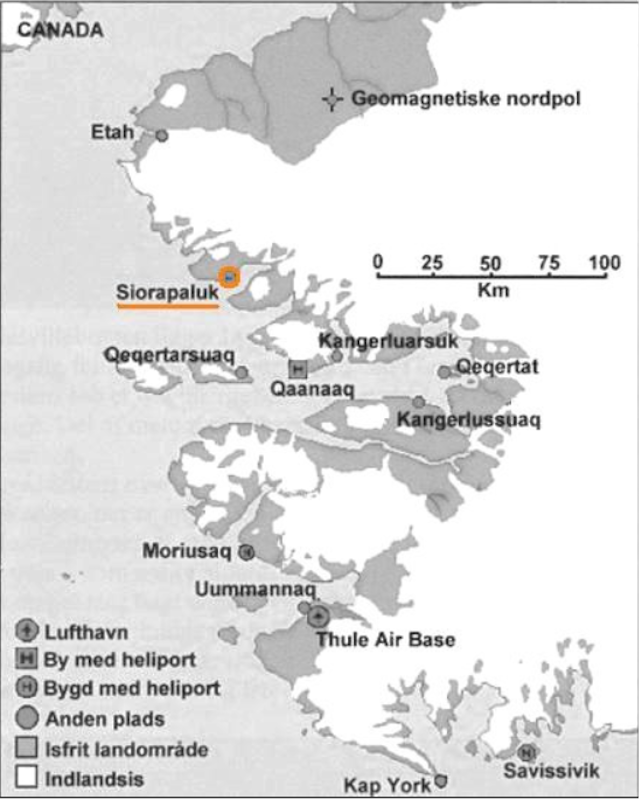

Qaanaaq, the northernmost residential settlement in Greenland.

Qaanaaq is the northernmost housing estate in Greenland, with a permanent population of 700 souls, and the second most northerly settlement. It is the closest permanent civilian housing settlement to the North Pole.

The colorful houses are built in rows and reach to the beach. There are no cafes or restaurants. But there are two traditional hotels for accommodation and food. There’s also a large market with all kinds of goods. There is also a souvenir shop for tourists when cruise ships stop by.

The large fuel tanks and the petrol station are located on the main dirt road which is an imaginary continuation of the wharf, going up the slope and dividing the village roughly in half.

The Earth may be round, and there is essentially no such thing as the End of the World, but if we wanted to give this designation to a housing estate then it would certainly be Qaanaaq.

Very close to the North Pole and hundreds of miles further north than other inhabited villages, Qaanaaq is surrounded by glaciers and fjords.

The waters in front of the village are permanently filled with massive icebergs.

The view from the apartment with which we were accommodated was good, but we never imagined that we would have to stay here stranded for so many days.

The first day was primarily dedicated to refueling, which was handled by Nuka, our new friend and gas station attendant. By late afternoon we were finished with the time-consuming and tiring fill-ups of our many portable tanks.

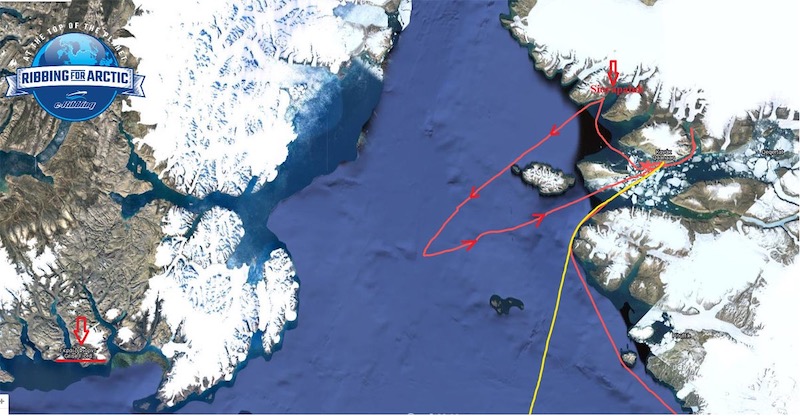

Nevertheless, we decided to tour the waters around Siorapaluk, the northernmost village in Greenland, since the next day we intended to sail to Grise Fjord in Canada.

The sun was up despite the late hour and the sea was calm. We eased out and began poking among the ice floes. We had not gone more than 5 miles (8 km) and found ourselves isolated again in the ice.

We tried in vain to find corridors for more than an hour before giving up and putting up the drone again to explore and take some photos of the ice and the cold sea.

Shortly before midnight, we retired to our apartment and stayed up late studying the weather conditions for the next day as well as the accumulation of the ice in the wider area.

DAY 34th – Friday, 5 of August

On a sunny Friday morning, the temperature reached 10 degrees C and the sea was flat. Ice reports indicated we could probably navigate through the ice fairly safely when approaching the Canadian coast.

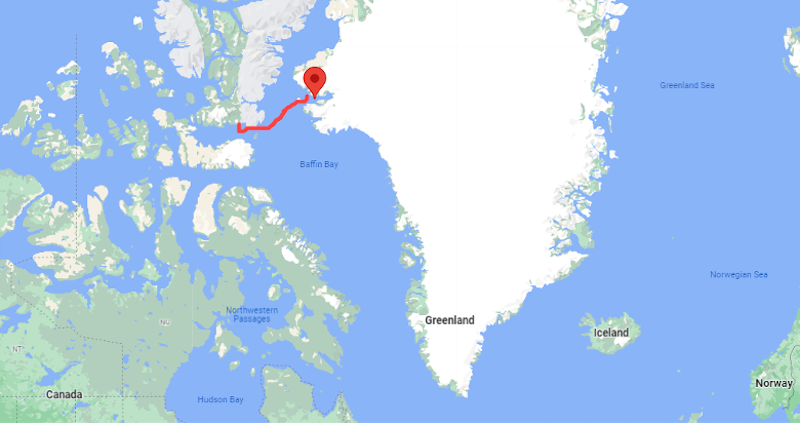

So we made the decision to leave Greenland after visiting first Siorapaluk, the northernmost settlement on Greenland. Siorapaluk is not inhabited year around—it’s primarily a summer settlement.

Note Thule Air Base which made famous in the 1950s as part of the SAC (Strategic Air Command) and the Distance Early Warning (DEW) line.

At 13:00, after a difficult navigation among the ice, we finally managed to reach Siorapaluk, which is very close to the 78th parallel.

A Danish frigate was anchored in the open sea near the village. We got close and for some time we talked with the skipper of the inflatable boat that was carrying the soldiers to the beach of the village.

Siorapaluk is a tiny village with 40 inhabitants, most of whom live here only in the summer months. With no infrastructure and only connection to Qaanaaq via helicopter, Siorapaluk is one of the most isolated settlements on the planet.

After a few moments of rest and the necessary photography, we turned our bow southwest towards Grise Fjord, Canada, some 215 nautical miles away.

Apart from the many icebergs we encountered on our way, the weather conditions were very good and the sun continued to shine. We cruised along at 30 knots. We were well rested and looking forward to reaching Canadian shores.

But our joy only lasted for about one hour. Suddenly we ran into a wall of fog. We were going again at 7 knots. It might have been the thickest fog we had encountered thus far.

Visibility was almost zero.

We might be used to it by now, but the sight of the ice popping out of the mist kept us completely focused. After a few hours I left Carlos and Cris in the pilot station and went into the cabin to rest.

I wanted to be rested for what was coming next. It was a good thing that I was.

After three hours of cruising, during which we covered only 18 nautical miles, the fog thinned considerably. We sped up again and were now traveling at 32 knots. But again, our good luck did not last.

Soon we came to a point where, as far as we could see, the ocean looked frozen.

Arriving at a Dead End

I spotted an open passage to our left and veered off course. We followed it no more than 20 minutes and the ice blocked our way again. I tried to head further east where another free passage opened up, but after a while we were blocked again.

We were constantly changing course but only managed to travel a few hundred meters. With continuous “slaloming” between the ice through channels that were getting ever narrower, we progressed slowly—but then the sea seemed all white everywhere.

I stopped the boat and we were trying to assess our situation against the current conditions. We had covered about 100 nautical miles and it was about that much farther to our destination. But there was no guarantee that if we continued on our course, the conditions would not get worse.

A Momentous Decision

Now, we had fuel to go back to Qaanaaq. But what if we went further and ended up trapped in the ice? Then there would be no option to return.

I realized that the large pieces of ice were being moved at a great speed by the strong currents. Some of the passages behind us through which we had passed were no longer there. The risk of being trapped was considerable, and we were literally in the middle of nowhere.

There was no one who could help us if we got blocked in.

The air temperature was 0 degrees Celsius. We felt what “cold sweat” really means just thinking about what could happen to us. Never before had we felt trapped in the ice to such a great extent. There seemed no solution.

After discussion, with great regret, we turned the bow back to the east again trying to find a way out of the ice and back to Qaanaaq. Our westward quest was at an end.

Heading East to Shelter

We picked our way back toward the east, again seeking the narrow channels between the ice that would allow us to travel in the right direction. After half an hour, with the help of radar we started to see open passages on our prow. We sped up to 30 knots, running to get away from the hell we had just experienced.

Just when we were beginning to feel sure we would at least make it back to Qaanaaq for fuel and shelter, we ran into another fog bank. It was still 50 miles to the settlement. There was no choice, we dropped off plane and eased along at 7 knots, focused on the radar and GPS.

At last we slowly entered Qaanaaq Bay—but we still had 20 miles to go to approach the village.

We were a long way from the dock, and we knew the reports indicated the concentration of ice here exceeded 50 percent.

With the fog it was impossible to get the drone up again.

Air temperature at 0 °C.

Water temperature at +1 °C.

Finally, the radar gave us the solution again.

We moved slowly and when our prow encountered an ice dam, we turned back and changed our course. This was repeated several times, until after many attempts we managed to reach a route that took us into the harbor, a very welcome sight, to say the least.

It was midnight when we retired to our apartment, incredibly tired, exhausted and disappointed. Without much talking we fell into a deep sleep. We wanted nothing more than to close our eyes—tomorrow we could deal with our situation.

The Adventure Continues -- Read Episode 14 in the next of BoatTEST’s “On the Water” Newsletter.