Ask Andrew: Diagnosing Battery Drain

Nothing ruins a warm summer afternoon faster than turning the key and hearing the clicking noises that surely indicate a drained battery. At this point – all that can be done is to charge the battery enough to start the battery and still enjoy the day.

But how was the battery drained in the first place?

Without being able to identify the source of the battery drain, it’s tempting to assume that the battery is deficient, and that it’s unable to hold a charge. But before investing hundreds of dollars in a replacement, lets examine how to test the battery, and how to track down the source of a piece of equipment onboard that may be draining the battery between visits aboard.

Two common scenarios explain how an unwanted battery-drain might play out:

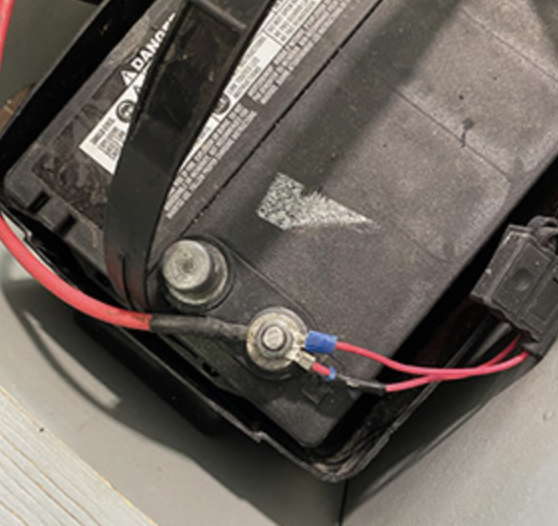

1) A trailerable boat: a bow-rider or a pontoon style boat. Typically a single battery will act to both start the engine and to power the electronics aboard. When looking at the battery, multiple wires will be connected. These will include such things as: The engine, the main fuse/breaker feed, the bilge pump, and perhaps added electronics.

As the boat sits unused for days or weeks at a time, there are a number of on-board items that may slowly drain the battery. Here are a few common culprits:

- The bilge pump (activated by a float switch): As water enters the boat (through rain or slow leaks), the float in the bilge rises, causing the pump to cycle on and off. If there is a high amount of rainfall over successive days, the pump will cycle on and off regularly until the battery drains down

- A stereo or fishfinder/GPS unit connected directly to the battery, and left on. Many manufacturers of these devices find that it’s simplest to write installation directions to wire the device directly to the battery, rather that to an on/off switch.

- A key-switch left on, powering the engine’s systems, and any other electronics linked to the key switch

- A device is installed that requires constant low-level power. More modern boats have GPS pucks, and ‘smart’ gauges that require a constant low-level current draw. If the battery isn’t charged regularly, over time, the battery will be drained

- A fault, corrosion built-up. The possibilities are numerous, and tests should be performed to track down the draw.

2) A larger cruiser or sailboat is a different animal often involving multiple batteries and a shore-power, battery charging system. In this case, the first indicator of a problem won’t be a dead battery. Rather, it will be a drastic shortening of a battery’s lifespan.

The battery may be drained in the same ways as the smaller trailerable boat – but you may not notice the drain because a dedicated battery charger is always plugged into shore-power. The result is that the battery is drained and immediately recharged. The charging cycles on and off resulting in a battery that can no longer hold a charge perhaps years ahead of schedule.

In whichever set-up you have, the first step is in identifying where the current is going. There is a simple test that can be performed using a multimeter that will allow you to isolate which wire(s) are drawing current: called an Amp-draw test.

Here are the steps to perform the test:

- Start at the battery and work ‘down stream’ from there to the fuse/breaker panels, engine and other systems

- Begin with the battery fully charged. Test the battery voltage using a multimeter, and record the voltage value (it should read somewhere between 12.4 and 13.5 Volts). Leave battery chargers off, and the boat disconnected from any shore-power source. Keep the key off, and all electronics off.

- Disconnect the wires from the positive (+) battery post. Set your multimeter to the ‘Amps’ setting. Separate the positive battery wires and prepare to test them individually, one at a time. Hold one multimeter lead against the positive post of the battery, and the other lead on each positive battery wire in turn. The value shown on the mutimeter will indicate if any amps are being drawn. A zero is a good thing: indicating that there is no draw. If any current readings are noted, mark that wire with tape and continue testing.

- If the marked wire runs directly to an appliance, you now have an answer. If the wire leads to a bus bar, fuse/breaker panel or junction, then the testing must continue, using the same process: connect the positive wires to the battery. Label and remove all of the wires at the junction/bus bar. Test each wire between the ‘feed’ and the ‘output’ using the multimeter to determine where current is being drawn.

- Continue moving downstream until the fault is found.

The off-season is a great time to track down and address some of these issues. In many cases, preventative maintenance is the key to bigger and most costly issues down the line. I would recommend performing an amp-draw test whenever a new appliance is installed or changed, and at the first sign of any battery drain issues.

As always, contact a qualified marine technician if you aren’t comfortable working through the test or repair processes.

Next issue, we look at fixing battery drainage