Bow Shapes Explained

Somewhat Perversely – and only during informal office – some of the design team in our busy Auckland naval architectural business manage to find any possible alternative to the correct, nautical term for parts of a boat. The forward sections of the hull are no exception, often and variously referred to as “the front”, “the sharp end”, “the pointy bit” – and possibly others that don’t immediately leap to mind. Call it a tribute to the legendary John Clarke’s ‘The Front Fell Off’ TV comedy sketch about a tanker that broke in half off Australia in the 1990s. If you haven’t seen it yet, you must. On issued drawings and specifications of course we call it the bow. Derived from Old Norse bógr meaning ‘shoulder’ and descriptive of the sections of a boat hull flowing forward from the broadest mid sections into the pointed stem and thus describing in general, the forward most parts of a boat hull.

Different Shapes

There is a seemingly endless variety of different bow shapes. Yacht racing in particular has seen changes over the last twenty to thirty years from classic long raked bows, to upright plumb stems and the latest move to backward raking – variously called inverted, destroyer or Dreadnought type bows, the latter named after the Dreadnought class of warships harking back to the beginning of the last century. Historically, the choice of bow shape in sailing boats has been heavily rule driven; designers respond to these constraints with shapes intended to maximize performance inside the legal boundaries imposed.

Those classic elegantly raked bows of the time meant that a sailboat measured well against the rules of the day where a short waterline length rated favorably, but was technically disadvantageous. Long overhangs at bow and stern meant that as the yacht heels to the wind, actual waterline length and thus maximum achievable boat speed increases. When the rules changed in 1990’s, so did bow shapes to the generally plumb stems seen in the intervening decades, when it became better to make waterline length as close to overall length as possible. Ships and powerboats of course have different constraints and operate quite differently – a powerboat doesn’t for instance operate at a steady heel angle as a sail boat on the wind does. In ships and power boats it is possible to see bulbous bows (below water), raked and flared bows (above water), plumb bows, axe bows, X bows, destroyer/Dreadnought (or inverted) bows, wave piercer bows – the list goes on. What does it all mean and how do you choose one bow type over another?

Similar Qualities

Bows need to have some or all of the following qualities: offer low resistance to motion through the water and thus best fuel economy in both calm and rough seas, minimize pitching motions and pitch slamming, minimize spray and wetting, offer lots of room inside the hull for accommodation, not let green water over the foredeck — the list goes on. So, the bow of a boat has a number of jobs to do — often a jumble of conflicting requirements that — as with so many elements of boat design – call for prioritization and compromise. A good solution for one problem can quite readily create new problems or less desirable knock on effects. Understanding the requirements of the proposed new boat and the owner’s expectations and priorities is thus a very important first step in the design process.

Often those expectations and priorities are born from well entrenched paradigms; before Steve Dashew burst into the passage maker scene with his ‘unsailboat’ FPBs, the market and industry would have described a passage maker motor yacht as a large volume, heavy displacement, wide beam hull, with big, bluff bows intended to lift over waves, where green water over the decks is not a good thing and pitching and pitch slamming are acceptable compromises.

These boats drew from knowledge gleaned over the years from small commercial fishing boats carrying heavy loads that evolved to handle foul weather, working offshore in sea states most pleasure cruiser actively avoid and where passage making speed isn’t necessarily that important. The forward raking and flared bow helps the hull to contour over the waves — the water plane area of the bow increases with height above water to achieve this purpose, so the higher a wave climbs up the bow, the greater the force lifting the head of the boat.

You don’t really want green water over a weather deck that has large open hatches into fish holds that can readily flood. That flare and increased water plane also means that a heavy displacement hull, with center of gravity and buoyancy well forward for fuel efficiency can assist to keep the bow from burying in following seas and worse, bow steering and broaching — although that isn’t an uncommon occurrence with this hull type.

Often, these hulls will have a bulbous bow under the water – and although these are sometimes used to correct static trim problems, or influence hull pitching behavior, their real purpose is to improve fuel burn, by reducing wave making resistance at passage making speeds due to positive interactions between the waves created by the bulb and the hull as they travel through the water.

Bulbous bows are generally good for a specific speed/length ratio and offer small gains that add up over a long period of time spent at the design speed. You don’t see too many large commercial ships without a bulbous bow these days and reduced fuel burn is the reason.

Knife Like

Dashew showed the world that you can have a long, slender, low wooded passage maker that wants to knife through waves to maximize comfort, with minimal power — and the ability to travel at significantly higher speeds than traditional long range cruisers when required. With measures taken to control roll motions you end up with a result that is for many, much better than the traditional alternative. If you structurally and hydro-dynamically design the foredeck and superstructure to deal with green water, then you can enjoy much better ride and sea-keeping qualities at the expense of the view out the windows being interrupted by solid water at regular intervals in rough seas (which isn’t actually as disconcerting as you might expect).

A long, slender hull allows for fuel efficiency with the longitudinal centre of gravity further aft, meaning that the fine bow can also pierce when running and surfing in a following sea without fear of broaching. Our Earthrace/Ady Gil wavepiercer design was a radical extension of this premise, where the very fine, knife like bow slices through oncoming waves to minimize pitch motions and allows higher speeds to be maintained in rough seas. Of course, as the world knows, the front fell off that boat too after collision with a large, steel whaling vessel, but not having first proven the concept over the course of more than two laps of the globe and setting a circumnavigation speed record that remains unbroken some 12 years later.

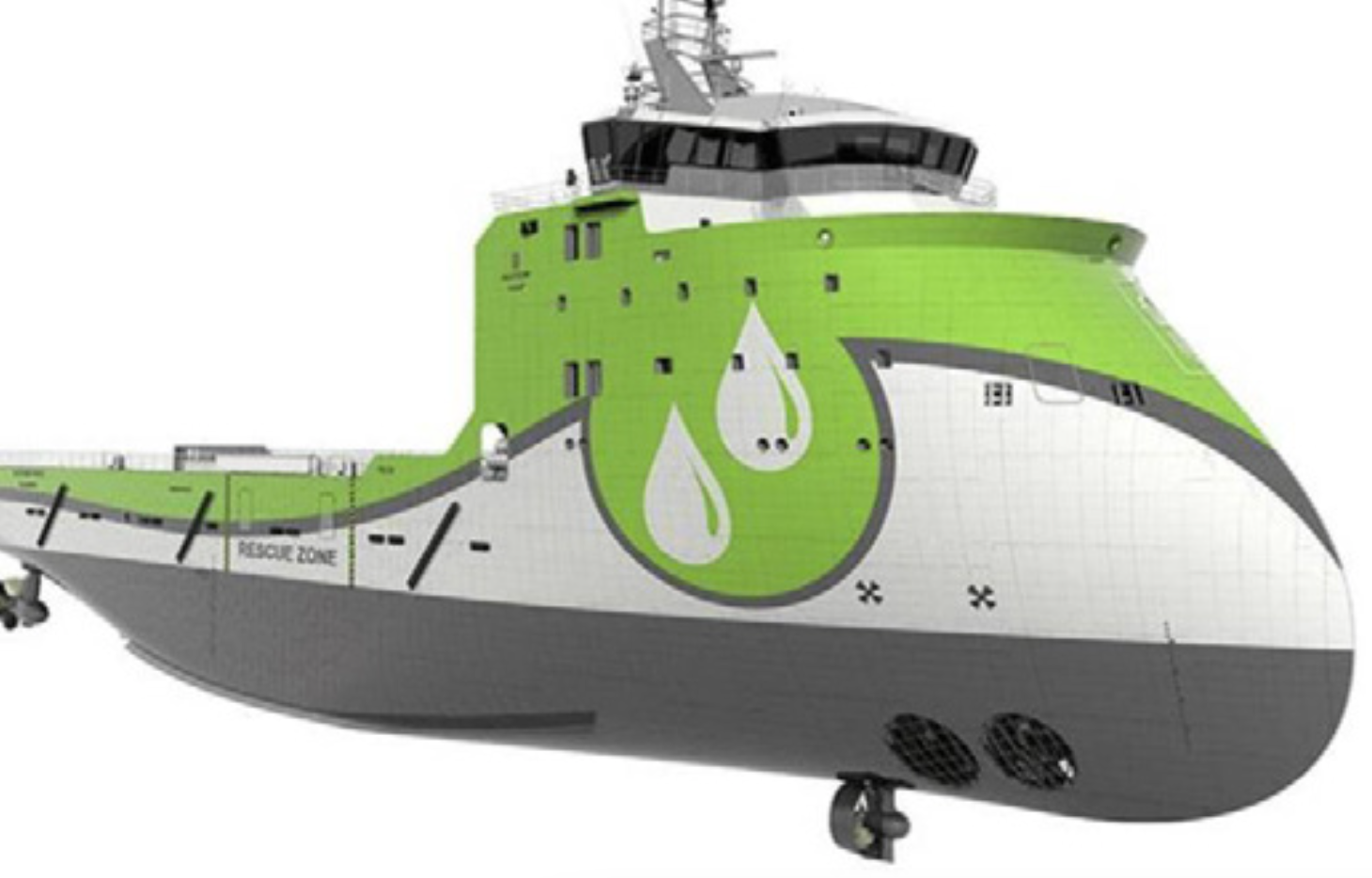

Wavepiercer Bows

We would tend to lump wavepiercer bows, axe bows, X bows, destroyer bows etc into the same basic category — the idea is to reduce waterplane area and volume above static waterline in the forward sections of the boat and offer a fine entry so as to reduce pitch response and slamming and thus improve passenger comfort and safety. How the boat is designed to deal with the volume of green water that is going to progress over the upper sections of the hull, decks and superstructure is where the distinctions lie between the different types.

Handling water that wants to track up and create spray can be difficult with all of these types of bow — and they do have a reputation for wetness. On a wavepiercer such as Earthrace, we streamlined the foredeck and windscreens, left them completely clear of equipment that could be washed off and designed the structures to handle the bigger water loads.

On a wavepiercer catamaran, it is only the forward sections of the demi-hulls that wave pierce — the large, monohull type center bow services to offer reserve buoyancy in following seas and helps shed spray. On Damen’s Axe Bow, they opt for a very fine entry and maintain hull depth — including a quasi bulb below water — with a relatively conventional foredeck, relying on the height of the topsides to send green water down the sides of the hull before it can turn the foredeck into a swimming pool.

On Ullstein’s X-bow, they offer an organically shaped ‘bonnet’, designed to shed green water before it can go places it shouldn’t, including a ‘last resort’ deflector to protect the aft placed foredeck. On the radical inverted bow motor yacht, A, there is a hydraulically operated wave deflector on the foredeck that lies flat for most of the time to retain the sleek styling of the forward sections of the hull, but which the crew can deploy in rough seas to encourage green water to return back where it came from.

Bow Shape Conundrum

The bow shape conundrum also exists for fast, planing hull power cruisers. For the hull designer, prized qualities of the bow include the ability to softly enter oncoming waves for high ride quality and to send spray aft and down to keep the boat dry, so a fine entry with low volume is good. Equally, the boat shouldn’t ‘dig in’ when running down wind or broach when surfing, where some ‘fullness’ in the bow is helpful. The interior designer will however differ and would argue that a full bow allows for more floor area, more cabin space, larger berths etc.

Commercial pressures have seen production motor yacht builders offering huge volume interiors for a given length of boat, with big double berths pushed well forward which can only happen with a bow shape that is full (i.e. fat) and which transitions to the stem very quickly. This inevitably compromises ride quality, leading to boats that tend to slam harder in head seas and push a big bow wave. For many owners, floor area and amenities are valued far more far than seakeeping qualities and the popularity of these boats underlines this thinking.

Patrol One

Some year ago we designed a 24m (78.74’) wavepiercer trimaran named Patrol One that was built and based in Mauritius. They used to do sport fishing charters to a small atoll some 250 miles (402.34 km) from Mauritius in typically rough, open ocean conditions and would complete the run there in around 10 to 12 hours. The wavepiercer ride quality made it possible to do this trip at night with charter guests asleep, waking up on arrival to a tropical Indian Ocean jewel that few can get to.

Later we heard of a local with a European 22m (72.18’) production built planing monohull with full bow sections who also did the run to St Brandon with his family, intending to shadow Patrol One. They got there in the end, albeit unable to operate at anything like a 20-25 knot average — and with some broken hull structure and joinery due to extreme slamming. The pounding and slamming they endured had manage to break open stores in the galley creating a huge mess — and to completely pulverize and juice a whole sack of potatoes stored up forward under the master cabin sole. I seem to recall discussions of divorce being threatened if the bloke attempted a repeat.

Plumb Bow Resurgence

The plumb bow has seen a bit of a resurgence in power boat design in the last ten years or so — perhaps driven in part by the move to vertical stems in the sailing world. Although it could be argued that styling and cosmetics play a large role in the adoption of plumb bows in powerboats, there are certainly some technical merits. A few years ago, we designed a prototype electric amphibian. This boat differed from others already in the market in that it could be towed behind a car on its own retractable wheels — essentially it carried around an integrated trailer that could also propel the boat on land via electric motors. Only those that have experienced Auckland’s boat ramp congestion will understand the joy of being able to launch your trailer boat, but not have to park a trailer in the next suburb.

At only 6m (19.69’), this was a small boat carrying a heavy load of tandem wheels, hydro pneumatic suspension, retracting undercarriage and wheel doors, drive motors, transmissions, batteries and controllers. Plus a 200-hp outboard and all the usual gear expected on a 6m (19.69’) runabout.

Most conventional runabouts have a raked bow which means that the overall length can be quite a lot longer than the water line length. And the shorter the waterline length, the less bottom-shell area you have to generate the dynamic forces associated with planing lift. So, on the Penguin amphibian with a limiting overall length of 6m (19.69’) to fit into a 20’ (6.1m) shipping container, we used the same basic underwater hull shape as the venerable Tournament 7m (22.97’) — but changed the above water hull shape to create a plumb bow. This allowed our 6m (19.69’) runabout to have the same load carrying capability and ride qualities of a significantly larger boat despite carrying much heavier loads than normal.

The Future

Where next for bow shapes? Your crystal ball is as good as mine although I think selection of different bow types will become more and more focused on application and best fit for purpose. Our work on un manned commercial and military vessels does give a little glimpse of the future, where not having to design a boat around people creates a number of freedoms in design — you don’t have to design hulls to wrap around people and their pesky need to eat, drink, sleep, shower, toilet etc.

You don’t have to worry about scaring them if the boat spends half it’s time underwater, or hurting them with slamming decelerations, so there is potential for us to design more and more radical boats with lots of options for suitable bow shapes to choose from. But there are still many of us that want to spend our leisure time relaxing on the water, so it is likely that we will simply see bow shapes on pleasure boats in the future following trends for whatever reason seems most compelling at the time.

Despite some good technical arguments for one bow shape or another, these things are often simply governed by what is fashionable. Plenty of people buy a pleasure boat based on how stylish it looks and how nice the interior is. We’ve seen that today’s modern inverted bows are just repeating history from the Dreadnought destroyers of a bygone era, so no doubt we will see similar innovations also come into and then fall back out of fashion once again. The important thing however – regardless of shape – is to make sure that the front doesn’t fall off…