Corrosion, Part 1: What Galvanic Means

It’s a scary thought, but if your boat is made of wood, fiberglass, aluminum or composite, it’s slowly deteriorating under you. Part of this is the nature of the marine environment: Sun, moisture, waves, wind, movement and vibration all contribute to components breaking down. But there are other factors that are more concerning and act at a significantly faster rate than the environment can take credit for. One of these is commonly spoken of, but not well understood: Corrosion.

Unseen Assault

As boaters, we’re concerned with two main types of corrosion: galvanic and stray-current. In this article, we’ll focus on galvanic corrosion. We’ll cover stray current in part two.

First, let’s be clear on what we’re talking about. Corrosion is defined as, “The gradual destruction of materials (usually a metal) by chemical and/or electrochemical reaction with their environment.” Galvanic is separated from stray-current by the manner in which this degradation takes place. Corrosion isn’t as simple as rust and it’s not delamination or rot. It’s not caused by waves, water or sun. It can’t be stopped by sanding, coatings and paints.

In a simpler explanation, corrosion is the return of a refined metal’s state to its more base form. The metals we use in boat building (steel, bronze, brass, aluminum) have been refined to their workable form. Corrosion is the natural process of these refined metals returning to a more stable form (oxides, hydroxides, carbonate or sulfide).

The important take-away here is that this is a natural occurring process — and refined metals will always work to return to these more chemically stable forms.

Compatibility Issues

One such process is called galvanic corrosion, where one metal corrodes preferentially when it is in electrical contact with another. Another way that the scientists define galvanic corrosion is, “When dissimilar metals and alloys have different electrode potentials and when two or more come into contact with an electrolyte, one metal acts as the anode and the other as cathode.”

Explained more simply, when two different metals are immersed in sea water, the stronger metal will steal electrons from the weaker metal. The electrons that are stolen show up over time as pitting or corrosion on the weaker metal.

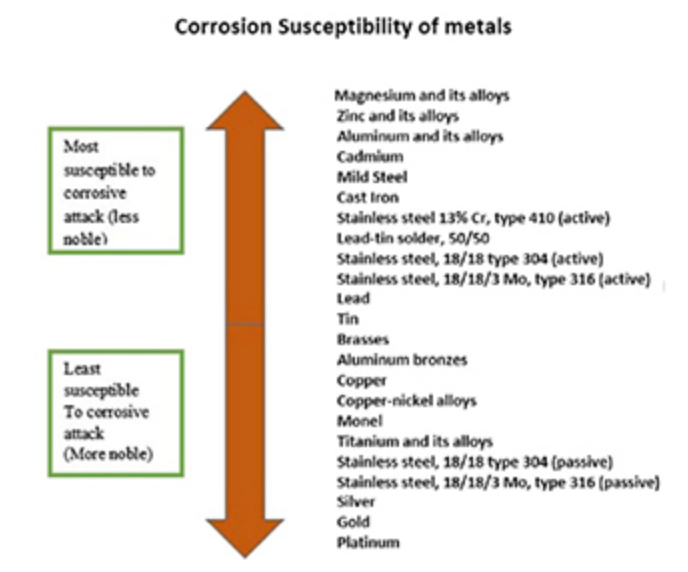

Which metal is the stronger metal? This can be found by referencing a galvanic chart, where metals are listed from strongest to weakest so that they can be compared and galvanic corrosion can be predicted.

Modern boats have the perfect storm for galvanic corrosion to occur: There are many metals of different strengths and a boat is immersed in an electrolyte. Reactions can take place between bronze through-hulls, steel screw-heads, steel prop shafts, aluminum propellers, steel and aluminum outdrives and components. Even the copper-based antifouling paints applied annually can create a reaction. The interactions between these metals underwater will allow corrosion to take place.

Sacrifices Made

But take heart. This is a known reaction with results that can be predicted and quantified. Safeguards were already put in place on your boat by the manufacturer before it was launched. It’s your job to help maintain these safeguards so that the natural galvanic corrosion that takes place can be kept at bay.

Here are a Few Ways That Modern Boats are Protected:

- The use of sacrificial anodes. This is when a “weak” metal (low on the galvanic chart) like zinc or magnesium is purposefully placed in locations where corrosion is likely to occur so it can be “sacrificed” in place of the more-important underwater metal components of the boat. By adding sacrificial anodes, you’re making it easy for corrosion to happen — but doing it in a controlled way. The key is to choose the correct anode type and to replace them on time so that the more important parts of your boat don’t become the anode.

- Electrically insulating metals from each other by using non-conductive materials between them. Covering screw-heads with a dab of caulking, using grease to coat metal components or fitting molded plastic over exposed metals can greatly reduce the likelihood of corrosion occurring.

- Cathodic protection systems — one example is the Mercathode system found on many MerCruiser stern-drive engines. This system used with the boat’s battery to run a low-level current through underwater electrical components. Each component is bonded to the adjacent section to let low-level current complete a full circuit. You’ll note that modern outboard engines and stern-drives have small gauge metal wires running from the transom assembly to the main drive to the trim rams. This is in an effort to oppose the corrosive galvanic current.

- Using similar metals. Note that galvanic corrosion only occurs when dissimilar metals are immersed in an electrolyte. If all underwater components are made from the same metal, the chemical reaction won’t take place. There’s a caveat, however: you must be aware of the underwater metals on the docks, chains, anchors and adjacent boats to ensure that this is effective.

In Part 2 of our look at corrosion, we’ll focus on stray-current and how to protect against it.

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College Mechanical Techniques — Marine Engine Mechanic program.