How to Choose an Anchor: It’s About More Than Weight

If you cruise long enough, the day (or night) will come when you will have to deal with your anchor dragging. It may be just a minor inconvenience or an embarrassing situation witnessed by amused fellow boaters, but it could also be something far more serious: the loss of your boat or even a life. The causes for this potentially dangerous scenario are threefold: inadequate ground tackle improperly deployed; a poor holding bottom or unsuitable anchorage; or deteriorating weather conditions.

Let us examine each in turn so we will be better prepared when, not if, the anchor drags.

Proper Ground Tackle

Unfortunately, many cruisers are not properly equipped for the conditions they are likely to encounter during an extended cruise. The excuses vary: “I don’t want excessive weight in the bow.” “I’m not strong enough to handle a big anchor.” “This is what the boat came with.” Or, “I can’t afford anything else.” Yes, anchors and rodes can be costly but they are one of the best investments a boater can make.

There are many anchor options available so be careful when choosing one. It is best to buy only bona fide products (not imitations) and ask fellow boaters what their experience has been with the type of anchor you’re interested in.

Anchor Types

There are the old standbys like the C.Q.R. (plow) anchor, the Danforth and the Fisherman’s. Then there are the newer options like the Bruce, Delta and Rocna anchors. There are a few others that are essentially developments on the original plow anchor.

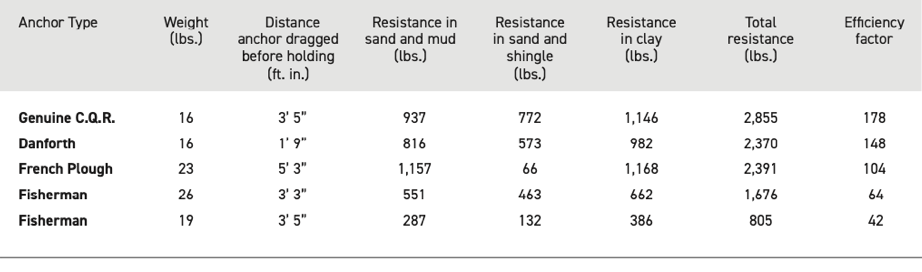

After the second world war, a French magazine undertook a test on the holding power of anchors available at the time in three types of bottom (see the results below). The efficiency factor of each anchor (shown in the right-hand column) was arrived at by dividing the total resistance in pounds by the weight of the anchor in pounds. It makes for an interesting comparison.

Anchors

C.Q.R. The genuine C.Q.R. (secure) was invented by professor, later Sir, Geoffrey Taylor, and consists of a single fluke in the form of two plowshares back to back. It was originally made by Simpson-Lawrence and is now available from Lewmar.

Danforth The American-designed Danforth anchor has two pivoting flukes placed close together with the shank between them and the stock across the crown.

Fisherman The Fisherman-style anchor was so popular with early yachtsmen that it is also called a yachtsman’s anchor. It is no longer as widely used as it once was and has the disadvantage of potentially fouling the anchor line on the exposed fluke if the wind or tide changes.

Variants It seems that every year, someone invents a new anchor but the modern plow variants, like the Delta (also available from Lewmar), the Rocna and the Bruce (also called a claw anchor) have earned good reputations to rival that of their progenitor, the original C.Q.R. The important thing, as the table illustrates, is that you choose a proven design and that different anchors perform differently in varying types of bottoms.

A Poor Holding Bottom

It is significant that, when tested, the French Plow had a resistance of 1,157 lbs. (524.81 kg) in a bottom of sand and mud and only 66 lbs. (29.94 kg) in a sand and shingle bottom. (Clay is an excellent bottom whereas fine, light sand is not.) Since we can’t always choose an ideal bottom, it is best to carry two or three anchors of radically different types: a bower that is the main anchor and a kedge about 2/3 the weight of the bower and, ideally, a second bower in case of an emergency. A light anchor that can perform admirably in a mud bottom may not be heavy enough to work down through a bed of eelgrass, for example, so what may be a poor holding bottom for one anchor may be fine for another.

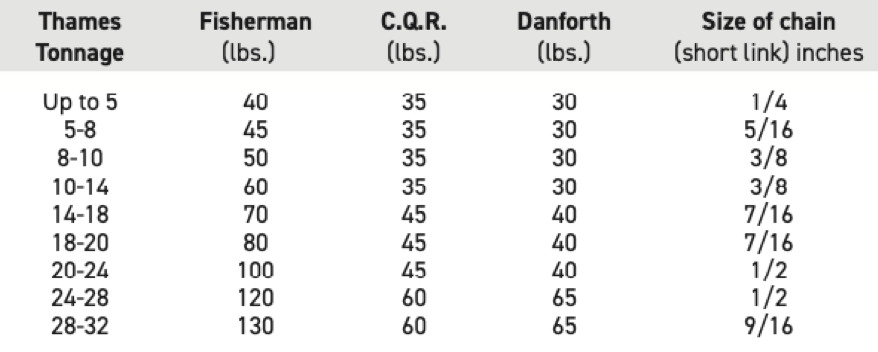

Anchor Weights The table below gives the approximate weights of bower anchors and sizes for chain for boats of different tonnages. It was developed by the late Eric Hiscock, who did a great deal to make boating a popular and practical pastime for the average person. There is much confusion about tonnage so be aware that Hiscock is applying Thames tonnage here which is not registered tonnage (such as appears on your vessel’s Certificate of Registry) or displacement tonnage (which is your vessel’s weight if put on a scale). Thames tonnage can be computed as follows:

(L.B.P. – Beam) x Beam x 1/2 Beam (all in feet)

94

L.B.P. is the Length Between Perpendiculars measured on deck from the fore side of the stem to the after side of the stern-post (on which the rudder is hung). It does not include a counter or canoe stern. It follows, for example, that a little traditional yacht like the Contessa 26 will come in at just under 6 tons TM, a Catalina 30 at 10 tons TM and a 39’ (11.89 m) Nordic Tug at 25 tons TM, approximately.

Hiscock was also of the opinion that it was unwise to use any type of patent anchor weighing less than 30 lbs. (13.61 kg), for although it may well have sufficient holding power when dug in, it may not be heavy enough to force its way through a layer of weeds. Since the C.Q.R. is not made in a 30-lb. model this will explain the discrepancy between it and the Danforth in the table.

Deteriorating Weather Conditions If we have chosen our anchorage wisely (not too deep and well protected from wind and waves), paid out at least seven times the depth at high tide in chain and employed an adequately sized anchor properly set in good holding, we have taken reasonable precautions against dragging. Unfortunately, if it starts to blow harder, we might still get into trouble.

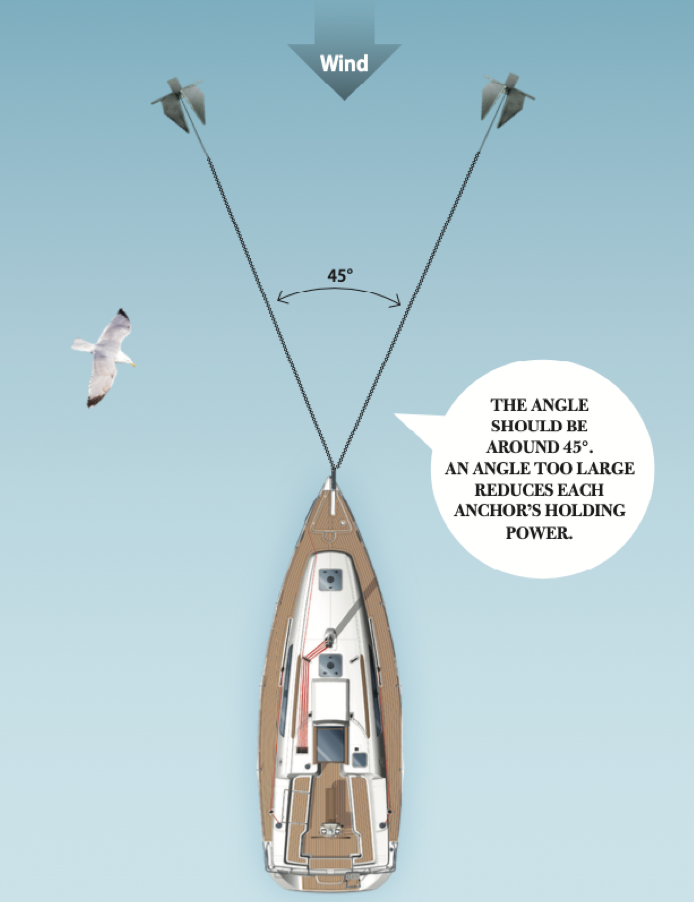

Given sufficient room in an anchorage, the first and simplest answer to severe weather is to pay out more anchor rode. This keeps the chain as horizontal as possible and reduces the stress caused by jerking on the anchor as the yacht sheers about in the squalls. Unfortunately, most anchorages, especially the good ones, are a little too crowded to permit you to pay out as much rode as you would like. Now is the time to deploy the second bower or the kedge, but this takes a lot more work and careful judgement than simply letting out more line. The trick is not to make the angle formed by the two anchors and the bow of your boat too large; if it is, you effectively reduce the holding power of each anchor. Old sailors knew this as the “swigging effect” and it is what allowed them to crank a heavy sail up the last few inches to get a taut luff. The halyard would be belayed and then a couple of deckhands would pull out and down to sweat up the sail. It is similar to pulling the string when notching an arrow on a powerful bow.

When deploying the second anchor, motor up until you are abreast and to one side of where you lowered the first anchor. Ideally you should drop the second anchor so that the angle at the bow between both rodes is not more than 45 degrees when the yacht settles back on them. Easier said than done in a strong wind, but if the angle is too great you exert more force on your anchors than you should.

Another weapon in the anchor-dragging arsenal is a “messenger” or “killick.” This is a weight that can be added to an anchor line some distance behind the anchor to keep the pull on the line as horizontal as possible. Almost anything will do if it’s heavy enough — a sash weight, a big trolling lead, a piece of trim ballast — but this ruse is pulled off far more easily in a yacht of modest size.

The Last Resort Still dragging? Start the engine and put it in gear ahead. I once rode out a notorious “Papagayo” wind in an anchorage in Costa Rica aboard the training schooner Pacific Swift with 500-lb. (226.8 kg) and 350-lb. (158.76 kg) anchors deployed, 150’ (45.72 m) of heavy chain on each and the engine roaring almost full speed ahead. I had a third anchor ready to swing out from a tackle attached to the end of the lower yard (so as not to foul the other two) when dawn broke with sufficient light to pick my way out among the reefs.