How to Choose A Fishfinder: Know Your Needs

How much do you know about your fishfinder? Most of us only make use of a few of the functions, but why not go all the way and learn just how amazing the modern units are? Gone are the days when all you got was a black and white display on a small screen that’s hard to read in daylight. Technology has made huge strides and what was the very latest last week is often superseded the next. Fishfinders are not just for locating fish. They are structure finders, position indicators and target finders. While they certainly show fish on the screen, they do much more. To understand everything about fishfinders, let’s start with the basics.

Different Types

A fishfinder is primarily designed to see a graphic representation of what is beneath your boat so it can identify the fish. To choose a fishfinder, first consider the type of fishing you spend most time participating in. Are you mostly targeting snapper in shallow water? Or are you seriously into chasing Kingfish or the occasional Marlin or Broadbill? Selecting the correct frequency for your transducer and appropriate power output at the outset will save disappointment later.

There are three fishfinder choices available; standalone models that perform no other function, combination products that also include a chartplotter, and fully-networked systems offering a smorgasbord of potential functions, all viewable through one or more multi-function displays.

Standalone Fishfinder: There are two ways of looking at this option. 1: You have limited space and budget and you just want a basic fishfinder. 2: At times your style of fishing demands a more hands-on approach. A quality standalone fishfinder will be simple to use and have dedicated knobs for manual control to give the best performance. In some cases, they have the option to network to a navigation system but still retain the standalone feel.

Combination fishfinder/chartplotter: Combo units make sense for most owners of mid-sized boats. Use GPS for navigation to the fishing grounds, view both on split screens. Sounder modules can turn many chartplotters into combo units with the installation of a transducer.

Networked system: Fully networked systems are available from all the major suppliers and usually will support a huge range of data sources including radar, raster and vector GPS charts and video. Many allow Bluetooth/WiFi, and can be controlled with a smartphone.

Your fishfinder, often an external “black box” module, is source of data. Multiple-display network systems are great for medium-sized or large vessels. The main advantage being the option to upgrade the system with new components as taste or budget allows. The capabilities get more amazing every year.

Fishfinder Display Specs

LCD displays are made up of a grid of “picture elements,” tiny dots that individually darken when electrical current is applied, with their name shortened in common usage to “pixel.” More vertical pixels mean higher depth resolution because each pixel represents less depth.

The number of pixels in the screen’s horizontal axis determines how long objects stay onscreen before they scroll out of view. This is particularly important with splitscreen displays that show narrow columns of side-by-side information.

More pixels per square inch will provide better detail of structures, a better representation of what’s below and improved split-screen images. More pixels — higher screen resolution and a big screen — let a user see the air bladders of smaller fish, see fish near the bottom, separate closely spaced targets from one another and view fish on the edges of “bait balls.”

But remember: the contrast of the display must also be sharp to use the resolution. Like many features, you get what you pay for with display resolution—the more, the better.

Fishfinder Screen Size

Most quoted screen sizes refer to the diagonal distance in inches across the screen. So a 12” screen is 12” or 30.48cm from corner to corner. As yet no manufacturer markets their screens in metric sizing, much like outboards are still in horsepower. Widescreen displays let us see more meaningful information when you split the screen to display more than one type of data, showing your GPS chart, radar screen, or returns from more than one transducer.

Power Plus

The power of a fishfinder—the strength of the “ping”—is expressed in watts RMS (root mean squared). Power is directly related to how well you see in silt-laden water, view down to greater depths and successfully resolve separate targets and bottom structure. A 500-watt (RMS) fishfinder should have plenty of power for most coastal applications. Serious bluewater anglers should look for 1,000 watts or more. Inland lake fishermen can see the shallow bottom with only 200 watts.

Fishfinders operate using a single frequency transducer, dual frequencies, multiple frequencies or a broadband CHIRP system. In general, higher frequencies give the finest detail resolution, the least background noise on the screen and the best view from a fast-moving boat, but don’t penetrate as deeply as lower frequencies.

Shallow-water inland anglers generally choose higher frequencies of 200kHz, 400kHz or 800kHz. For maximum depth, use lower frequencies. 200kHz or higher (up to 800kHz) is good for water depths up to 60m and 80kHz or 50kHz for deeper waters. In some applications like fishing in deep water for Broadbill, a combination of 2 to 3 kHz of power and a 38kHz transducer is proving to work very well.

CHIRP and Broadband

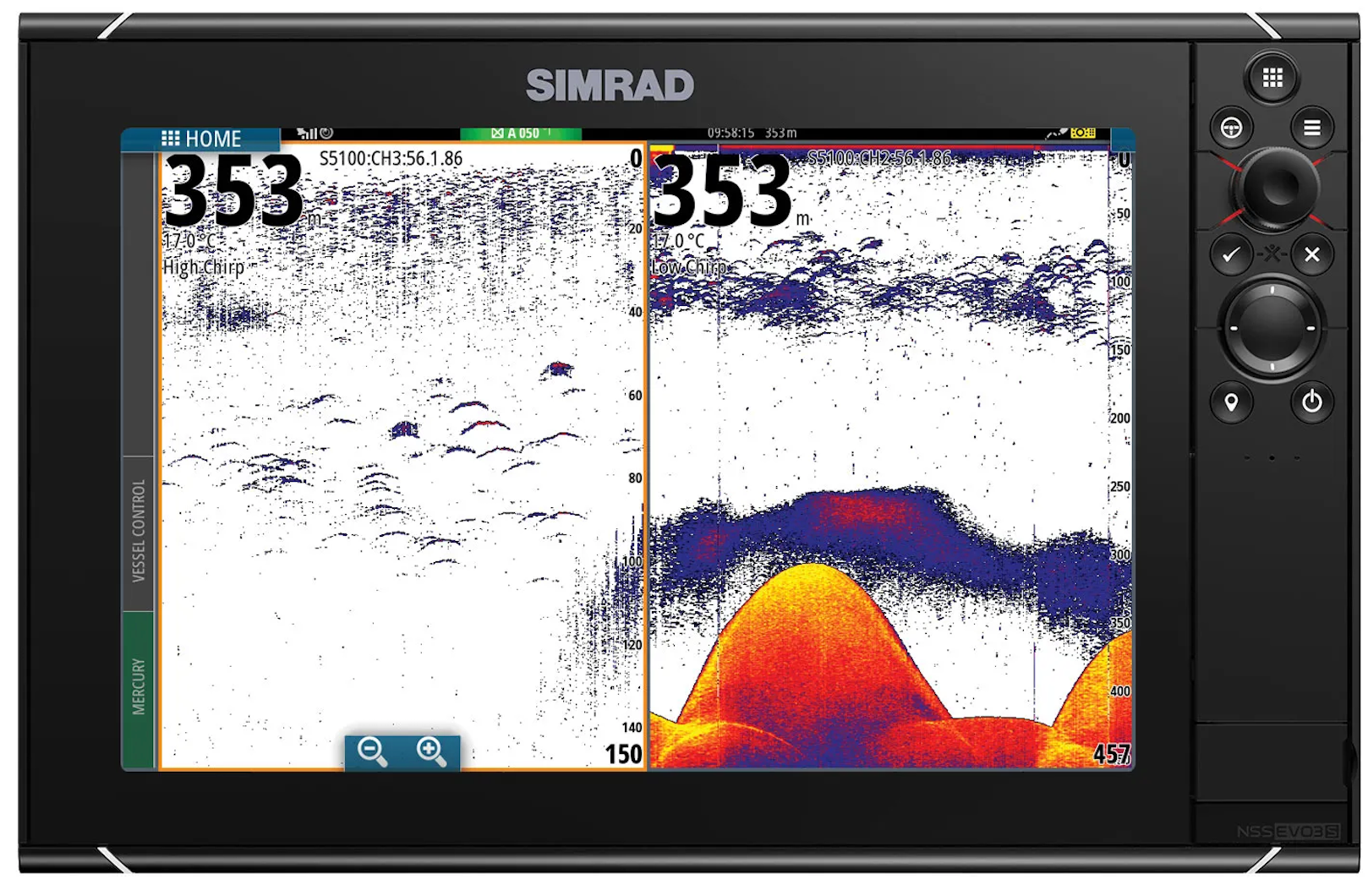

The newest style of broadband fishfinders, commonly called by the acronym CHIRP (Compressed High Intensity Radar Pulse) don’t transmit on just one or two frequencies. Instead of transmitting only 200 or 50kHz, for example, CHIRPing devices transmit a signal that sweeps linearly upward (from 40 to 75kHz, 130 to 210kHz, or other frequency ranges).

CHIRP fishfinders transmit less peak power than a conventional fishfinder, but their wide-band, frequency modulated pulses (130-210kHz, for example,) can be longer in duration and put 10 to 50 times more energy into the water. Using digital pattern matching and signal processing, CHIRP devices achieve unprecedented resolution and target detection.

Your ability to resolve individual fish, or separate fish from bottom structure, is now a matter of inches or centimeters instead of several feet or meters with traditional fishfinders. You can now see individual fish in groups, instead of a single mass. Depth ranges of nearly 10,000’ (3,000 m) are standard with these broadband devices. These sounders feature dual-transceivers that allow for simultaneous and independent dual transducer operation. This permits customization so a user can CHIRP or dial each transducer into specific frequencies.

CHIRP devices can transmit simultaneously on high and low frequencies. The lower frequency gives greater depth penetration and it requires less power than the higher frequency signal so it generates less noise. The result is a “whisper into the water” that locates the fish without disturbing them. The higher frequency signal gives even finer detail at shallow to mid-water depths. You can select from a range of frequencies to best suit the conditions in which you are fishing.

Changing Direction

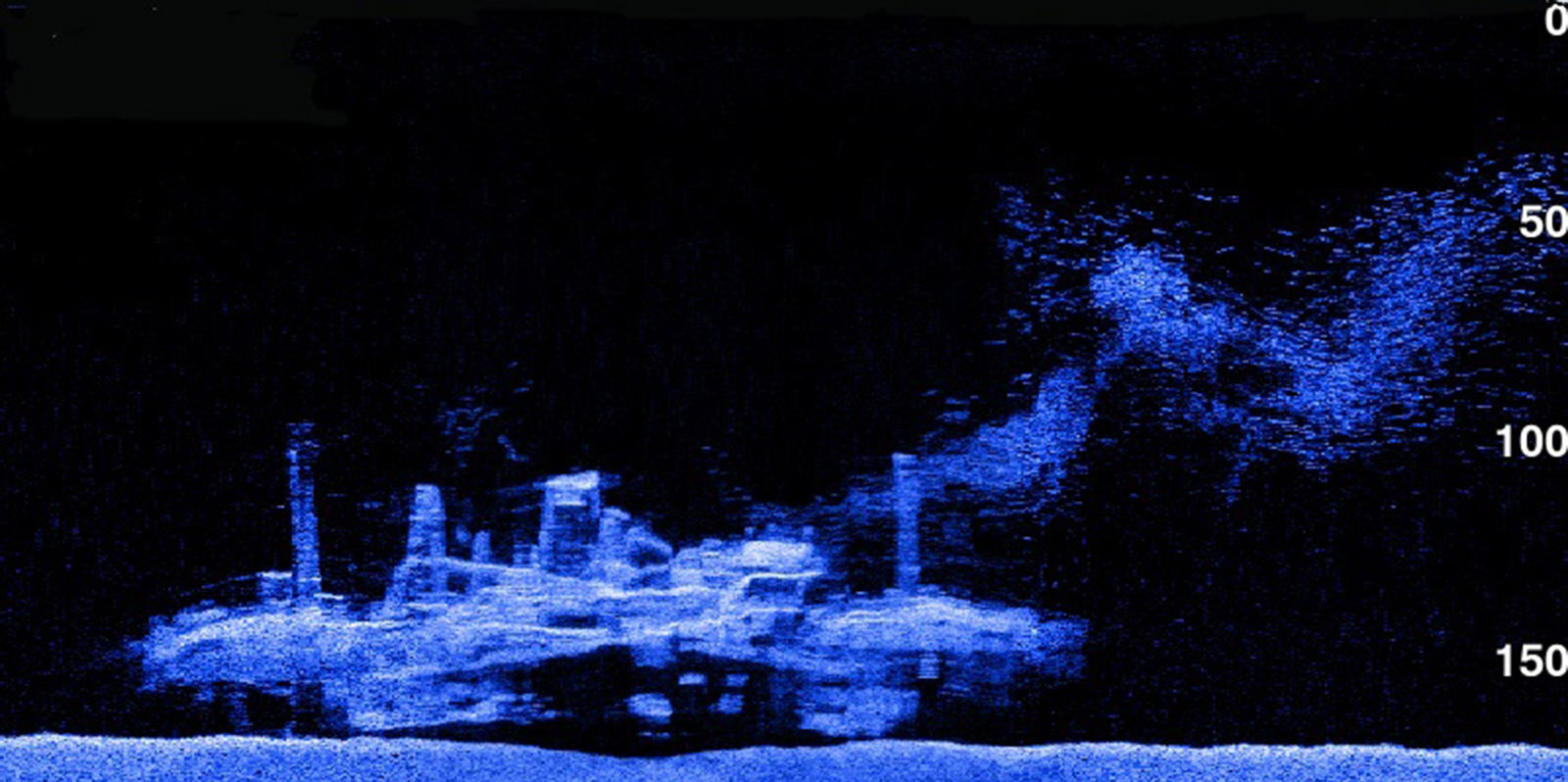

Fishfinding has changed, with high-frequency (400 or 800kHz) transducers that look to the side, straight down or can aim over a 360-degree range. Fishfinder manufacturers offer a growing (and often confusing) assortment of choices in frequencies, beam widths, and now even the underwater direction of the view. Anglers who search for fish in shallow waters don’t need the power to see down to 5,000’ (1500 m) but can gain a big advantage by looking out to the sides, so products using multi-beam transducers are ideal for that purpose. Here’s where the marketing jargon takes over, with names like StructureScan HD and DualBeam PLUS.

Transducer Talk

Arguably the transducer is the most important part of a fishfinder. There are many options and it’s crucial that a user select the correct transducer to suit a fishfinder and its features. It can seem complicated, but it needn’t be. To better understand this transducer mumbo-jumbo we’ll review some basic theory, courtesy of the folks at Airmar who make the transducers just about everyone uses: Higher frequency transducers have shorter wavelengths and more wave cycles per second, which means you can visualize more details (smaller fish), but have only shallow-to-moderate depth capacity. One sound wave at 200kHz is slightly longer than 2.5” (63 mm) so 200kHz sound wave will be able to detect fish as short as this length.

High-frequency provides a crisp, clear picture of the bottom with the tradeoff of less depth range. Lower-frequency transducers, with longer waves and fewer waves per second, show less detail (larger fish) but carry more energy and penetrate to greater depths. One sound wave at 50kHz is slightly larger than 1” (2.55 cm), so a 50kHz sound wave will only detect fish if their air bladders are large, slightly longer than an inch. Lower frequency won’t provide as clear of a picture but will operate effectively in the depths of the ocean.

There are also a number of ways you can mount your transducer and while most trailer boats will see that on the transom, larger boats usually go for thru-hull mounting. Thru-hull is the most challenging to install, but likely to provide best signal quality. Displacement powerboats generally use thru-hulls. A thru-hull triducer contains depth and temperature sensors, plus a speed paddlewheel.

Transducer

Trailer boats are more likely to have a transom-mount, with an adjustable-angle bracket screwed or bolted to the transom, with transducer hanging below and behind the hull. It’s a very simple installation, but you often encounter more turbulent water flow at speed.

Then there is the in-hull, “Shoot through hull” transducers that need no direct water contact. They are glued to the inside of the hull with silicone or epoxy. They do not work on cored hulls or steel hulls, only for solid fiberglass.

Be aware that using a transducer in-Hull will compromise the fishfinder’s depth capability and disable features such as Accu-Fish and Bottom Discrimination, which require the transducer to have direct water contact. Accu-Fish and Bottom Discrimination let a user analyze the size of fish targets and to establish the bottom composition right below your boat.

Options Aplenty

When deciding on a fishfinder, check out all the options. Consider firstly how much real estate it is going to take up on the dash, or if bracket mounted, just where are you going to mount it so you can see it while driving?

Cost is also a major factor, with a very basic color fishfinder retailing for less than $200, right through to MFDs (multi-function displays) that can set you back over $20,000. However, there is a huge lot of options between, it’s just a matter of finding what suits your budget, your boat and your needs.