Marpa For Collision Avoidance

Imagine cruising in busy shipping lanes and then the fog comes down. It can easily happen on the East Coast north of Boston where the cold water currents coming down from the north meet warm moist air blowing up from the south. Fog can also be a hazard on the West Coast so no matter the location, a captain needs to be prepared to cope with it.

Use Radar

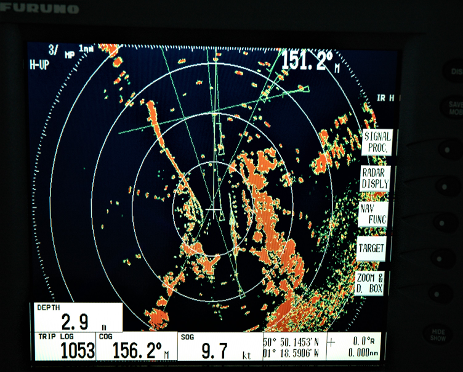

The first thing a captain needs to do is turn on his radar. It is the most important navigation aid in fog. It tells him where the other vessels are and shows the land features so it can act almost like a second pair of eyes. The problem with radar is that what appears it must be interpreted and nothing can be taken for granted.

Most captains use radar in ‘ship’s head-up’ mode which displays the bow at the top of the display. It is the logical way to picture what is around the boat and the vessels that are in the vicinity will show up in the places where they would be visible by looking out the window. The captain must work out which of these targets poses a collision risk and more importantly, which ones require a course alteration under the Colregs which govern collision avoidance actions in both clear weather and fog.

MARPA To The Rescue

The basic mantra for establishing the risk is: If constant bearing and decreased range then there’s a risk of collision. It’s easy to say but hard to do in crowded waters. This is where MARPA can come in handy. Many small-boat radars have a Mini-Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (MARPA). It’s a simplified version of the collision avoidance systems that the big ships use on their sophisticated radars.

MARPA can provide the target’s Closest Point of Approach. The CPA can give an instant indication as to whether any selected target presents a collision risk. If the CPA is less than half a mile, a captain should be concerned and if it is less than a quarter of a mile it is time to do something about it. A captain should be mainly concerned about the targets to starboard because those are the ones he is trained to give way to. Keep an eye on the others because they may get too close for comfort

Large ships have Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA) to do much of the work for them. The principal difference between ARPA and MARPA is that ARPA carries out this type of target analysis with every vessel target on the display. With MARPA, the user must select the specific targets and the system can only cope with a certain number of objects, usually about 10 which is more than enough for most practical purposes.

Not Perfect

In theory MARPA should do much of the work when dealing with targets but it has drawbacks. First, there is a delay between selecting a target and the radar showing what should be a reliable result. This is because the radar takes time to acquire the average course and speed of the target from which to do its calculations. The longer the target is assessed, the more accurate the results are likely to be.

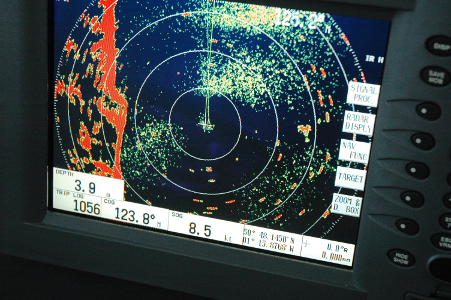

For MARPA to work properly, the host vessels needs to be maintaining a consistent course and speed. This should not be a problem, except perhaps on a sailboat where wind gusts or lulls might affect it although it would make sense to switch the motor on in fog anyway. To stay on a consistent course, it would be logical to be steering under autopilot which is a good thing to do in fog anyway so that you can focus on the lookout and collision avoidance.

One hidden problem associated with MARPA relates to the speed and course input. This input to the radar should be the speed and course through the water, not the speed and course over the ground.

Select the Proper Input

However, a captain is likely to find that the normal input for the radar will be the speed and course over the ground (SOG) because these numbers are those that are the easily obtained from the GPS. Getting the speed and course through the water, which is known as sea stabilization, requires a good quality log and a compass with the readout from the latter showing the true rather than the magnetic course.

The difference between ground and sea stabilization is less of a problem for faster craft, typically those doing more than 12 knots because the difference is usually quite a small proportion of the boat’s speed. However, for sailboats and most displacement power cruising boats the difference can affect the MARPA considerably and produce unreliable results particularly in areas where the current runs strongly. It is, however, also something that must be considered even in a faster boat if, for example, speed is reduced in fog.

The difference between sea stabilization and ground stabilization is caused by the effect of the tide and current on the speed of the boat. Out in the open ocean, there may not be much influence from currents except perhaps in the Gulf Stream but if someone is transiting the Florida Straits then the current can be significant.

When navigating on a slow boat in area where there are significant currents then AIS may give more reliable information about another vessel’s course and speed. However, this information is also ground stabilized and it will not give a reliable indication of the all-important CPA. Don’t give up on the tried and tested solution of running on autopilot and putting the variable bearing marker (VBM) on the target. That VBM on the target will help establish any change in the relative bearing of the target which is still a good indication of whether risk of collision exists just like it says in the Colregs.

Finally, regardless of the system being used to establish the collision risk, take action in good time before the two vessels get too close and always keep an eye on the other craft because he may be taking avoiding action because there is another vessel nearby that is posing a collision risk to him. The captain must take action in a common sense and seamanlike way and there is no sense in maintaining course and speed and then having a collision simply because he feels he was in the right. Nobody wins in that situation.