Quest for the Northwest Passage: Series Introduction

In order to put the voyage of Thomas P. and his crew in proper perspective, it is important to know a bit about the history of man’s quest to find the Northwest Passage. For over 400 years sea captain-adventurers attempted to find the illusive route between ice and islands in the far north. Following is a brief outline of that pursuit.

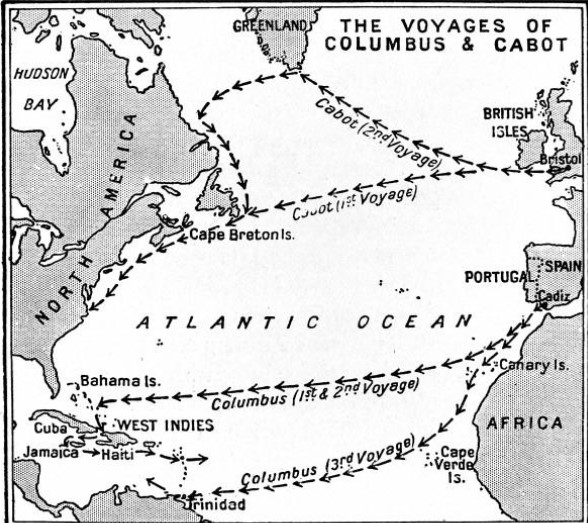

John Cabot. The quest for a passage from Europe to China and the Far East dates back to Columbus in 1492, of course. But it was John Cabot, a Venetian navigator living in England, who became the first European to attempt to find Northwest Passage through the earth’s northern latitudes in 1497. On his second voyage he got as far as Labrador.

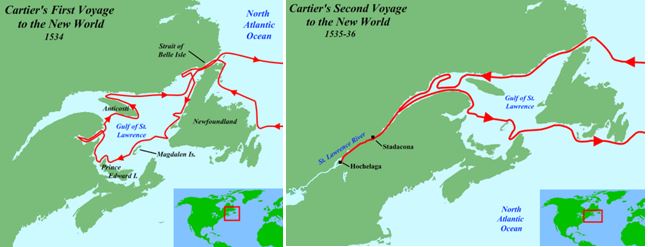

Jacques Cartier. In 1534, King Francis I of France sent explorer Jacques Cartier to the New World in search of riches…and a faster route to Asia. His first attempt took him into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and his second was up that river. Cartier’s voyages of discovery claimed what is now Canada for France.

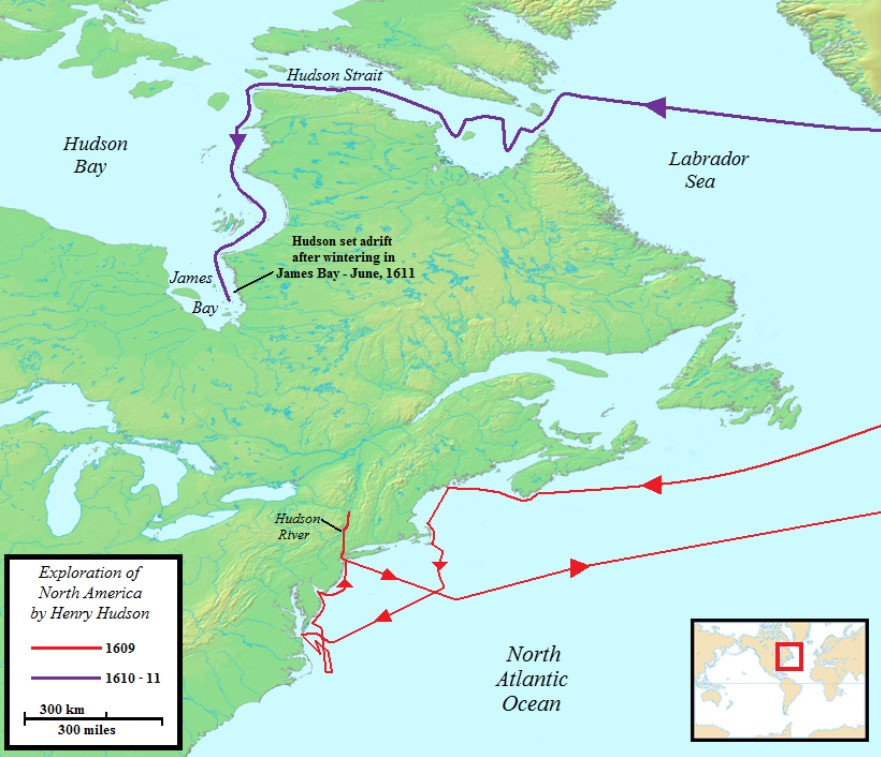

Henry Hudson. In 1609, the merchants of the Dutch East India Company hired English explorer Henry Hudson to find the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific. On his first voyage in 1609 he visited Delaware Bay and the mouth of the Chesapeake and the Hudson River and realized that the “Passage” must be farther north.

On his second voyage in 1610-11, he was more on the right track, navigating Davis Strait between Baffin Island and Labrador. Sailing on west he discovered the huge bay that now bears his name. Further exploration by Hudson was cut short in June 1611 when he was set adrift in a small by his mutinous crew. On its way back to England the crew stopped at an island in the mouth of the bay, was set upon by indigenous people and several were killed. The rest returned to England and escaped punishment. (The route to the East around Cape Horn was discovered by the Dutch in January 1616.)

Capt. James Cook. In 1778, on Capt. James Cook’s third and final voyage of discovery he attempted to find the Northwest Passage travelling from west to east. By the second week of August 1778, Cook was through the Bering Strait, sailing into the Chukchi Sea. He headed northeast up the coast of Alaska in the Arctic Sea until he was blocked by sea ice at a latitude of 70°44′ north.

The Great Franklin Northwest Passage Expedition

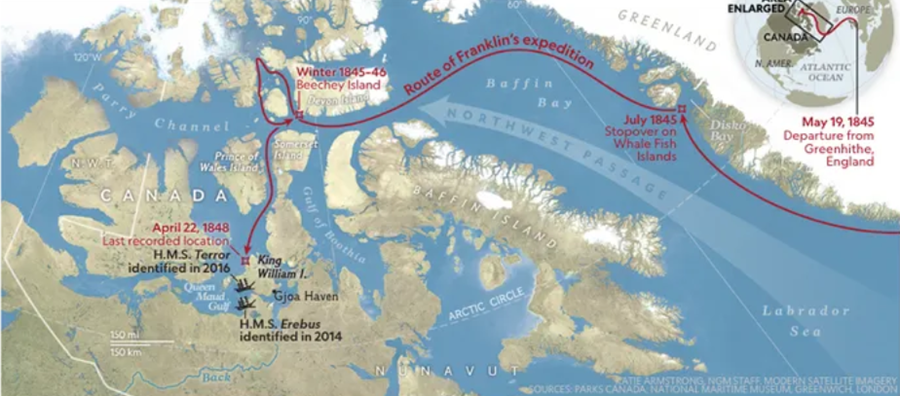

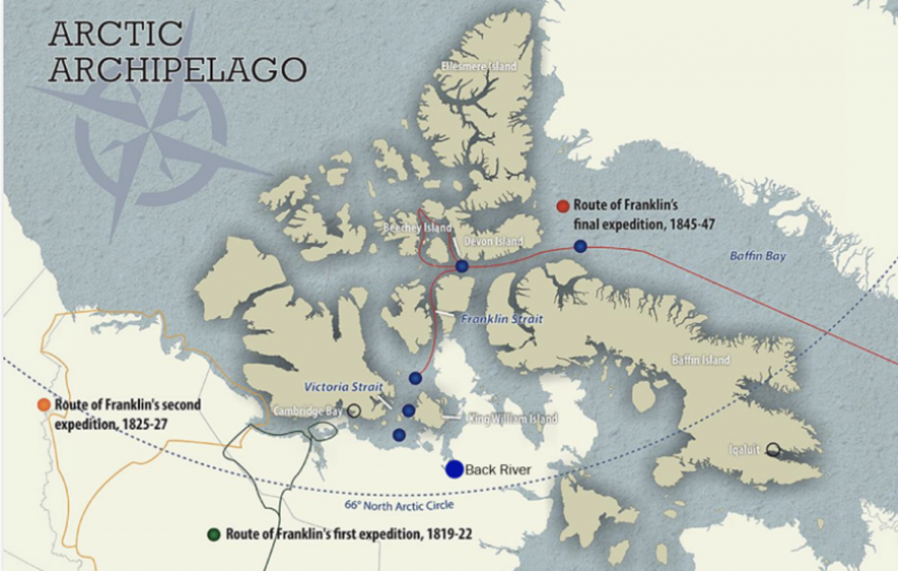

Sir John Franklin. The most tragic Northwest Passage expedition was led by English Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin in 1845. Franklin’s expedition set sail with 128 men aboard two ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror.

Winter 1845-46. Having ascended the Wellington Channel, in the Queen Elizabeth Islands, to 77° N, the Erebus and the Terror wintered at Beechey Island (1845–46).

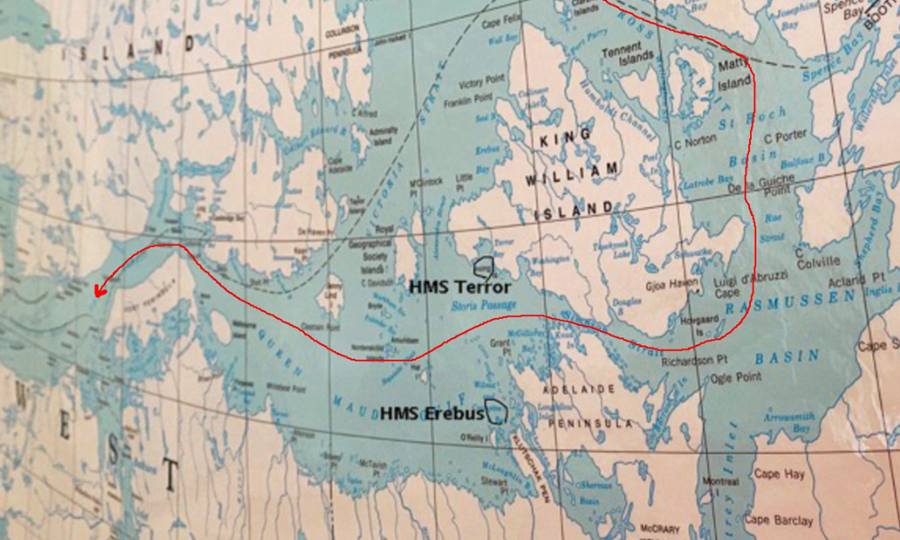

Summer 1846. In the 1800s, the navigable season was usually short, if it existed at all, which some years it did not. In 1846, they traveled South through Peel Sound and Franklin Strait. In September 1846 they became trapped in the ice in Victoria Strait, off King William Island (see below).

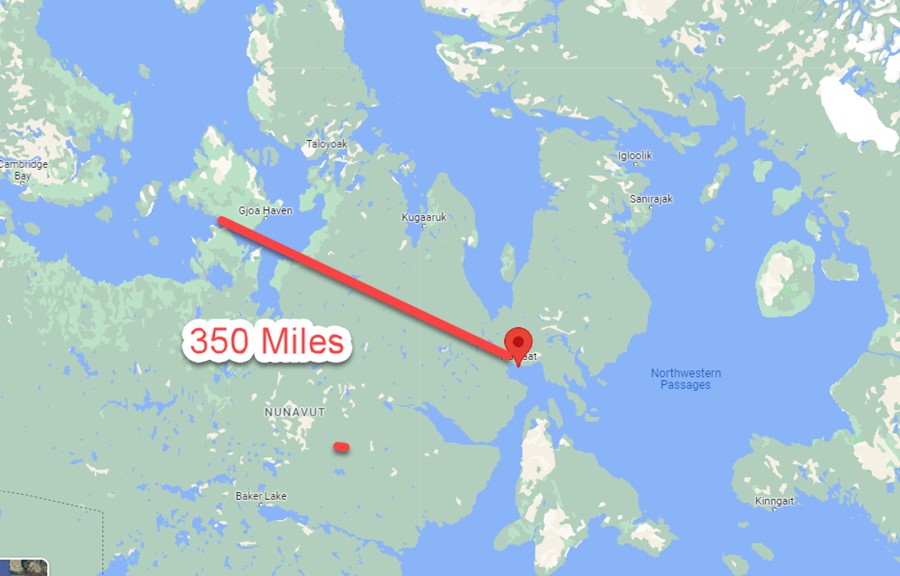

Overwinter #2 1846-47. Both ships overwinter 1846-47 trapped in the ice to the west of Somerset Island and the Boothia Peninsula, about 350 miles (560 km) further south than the previous winter at Beechey Island. Inuit testimony records that the Terror was heaved onto her beam ends (on her side) by the ice. All crew wintered on the Erebus.

The ships were iced in on the 12th of September 1846.

1847, Year #3, May 28. A note was found from this date that says "All Well". The death toll to date seems to have been 3 more men, in addition those who died on Beechey Island.

June 11. Sir John Franklin, age 61, died of natural causes, the total death toll at this time was 24 men.

Overwinter #3, 1847-48. Explorer and would-be rescuer John Rae interviewed local Inuit several years later, and was told that the dead were placed in the abandoned Terror which became a mortuary ship.

1848, Year #4, April 22. Erebus and Terror are deserted having been "beset" (frozen into the ice without release) for around 19 months during which time they drifted 9 miles. (The ships later sink some 80 miles apart, after being crushed in the ice.)

1848, April 25. Captain Crozier, 51 years old, second in command, and veteran of six arctic and Antarctic expeditions, and Capt. Fitzjames, make a written record (around the margin of the previous one nearly a year earlier). They say they intend to walk to the Back's Fish River setting off the next day, the 26th. There were 105 survivors at this time.

1849, Year #5. Inuit testimony given those hunting for Franklin several years later reported that the Erebus was occupied again in spring 1849 with the Terror still on her beam ends. The crews had started to fragment into smaller parties now, in part according to strength and health it was noted.

1849 to 1850. According to the Inuit, surviving crew hunted birds and caribou in the summer and seals in the winter. They had taken supplies for 3 years which were now exhausted. Good relations seem to have developed between the reaming crew and local Inuit with at least one very successful joint caribou hunt.

Captain Crozier is thought to have died sometime during 1849-50 winter and to have been given a military burial as witnessed by some Inuit.

1850. In 1850, the still intact Erebus now released from the ice was taken south with a very small crew in the command of a physically large officer, possibly Captain Fitzjames, or Lieutenant Fairholme. This man died shortly after arrival in Wilmot and Compton Bay on the west side of the Adelaide Peninsula as described by Inuit who found him in the great cabin.

The remaining crew sought out animals to hunt in the summer both here and by boat to the west. There are several accounts of "white men" who tried to hunt but died.

1853. The following information is from a report by John Ray who spoke with Inuit in 1853 and posted his report in York Factory, on the Hudson Bay in 1854. The Inuit he spoke with had not seen any of the Europeans themselves, but received the information from the Inuit from which they received about 50 articles that belonged to the ill-fated men. Rae personally saw and obtained the items, and listed them in his report.

“…Inuit hunters saw 40 white men dragging a boat on a sledge, the Inuit sold the men a seal for food. The Inuit also tell of a later date in the same season of many dead men and of signs of cannibalism.” (Which were later proven by forensic studies.)

“In the summer of 1851 or 1852 the Inuit report that there were four remaining survivors, being the best of the hunters accompanied by a dog used to locate seal holes in the ice. They set out for the west and are not heard of again.” This is thought to be when the last survivors from the Franklin Expedition finally died.

Franklin himself never proved the existence of the Northwest Passage, but a search party sent to find him from west to east, proved that there was a water route, if only it wasn’t iced over.

Roald Amundsen Finds the Holy Grail

In 1903, Norwegian Roald Amundsen led the first expedition to successfully traverse Canada's Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. He planned a small expedition of six men in a 45-ton fishing vessel, Gjøa, in order to have flexibility. His ship had relatively shallow draft. His technique was to use a small vessel and hug the coast.

Amundsen had the boat outfitted with a small 13 horsepower single-screw paraffin (diesel) engine.

Gjoa traveled via Baffin Bay, the Parry Channel and then south through Peel Sound, and James Ross Strait to the south east coast of King Williams Island and wintered over in what is now called Gjoa Haven, in remembrance of Amundsen’s two winters spent here.

During this time, Amundsen and the crew learned from the local Netsilik Inuit about Arctic survival skills, which he found invaluable in his later expedition to the South Pole (he was the first to reach it, Dec. 14, 1911, beating British Robert Scott by over a month.) For example, he learned to use sled dogs for transportation of goods and to wear animal skins in lieu of heavy, woolen parkas, which could not keep out the cold when wet.

Today, several inhabitants of King William’s Island claim Amundsen as an ancestor and have blue eyes to prove it.

Leaving Gjoa Haven, he sailed west and passed Cambridge Bay, which had been reached from the west by Richard Collinson in 1852. Continuing to the south of Victoria Island, eventually finding its way to Alaska and Nome.

2022 – Arctic by RIB

Thomas P. and his companions were out to document the ravages of global warming on the planet in the arctic where temperatures have risen more than on the rest of the earth. The trip would also prove the durability and seaworthiness of their Seafighter 36 RIB and twin Suzuki 350-hp outboard engines. Obviously, adventure was also one of the objectives, and testing one’s endurance against the elements in one of the planet’s most unforgiving environments was as compelling as any other reason for the voyage.

BoatTEST is proud to bring to our readers the remarkable story of this boat’s voyage and of the trials and challenges that the crew faced going to the “Arctic by RIB.”

Tomorrow – Antwerp to Scotland