Seagrass on North Carolina Coast in Jeopardy

A small net dipped into a patch of grass submerged in shin-deep water near the edge of a salt marsh on the central North Carolina coast. Retired National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist Jud Kenworthy of Beaufort, N.C. lifted the net to reveal a colorfully striped juvenile pinfish, no bigger than a pinkie, among the strands of green and brown vegetation.

Pinfish are among dozens of fish species residing in estuaries for part of their lives, grazing on underwater grasses. Eventually, schools of the small fish, distinguished by a sharp dorsal fin, will spawn offshore in large groups and be hunted by predators: groupers, snappers and dolphins.

The Natural Cycle

Their journey ends when hooked by a recreational angler from a pier or captured by a commercial fishing vessel to be used as bait for a bigger catch.

But the pinfish depends on the rich estuarine habitat that flourishes along the North Carolina coast — an ecosystem that relies heavily on a meadow of grass covered by 12 inches of salt water where land and sea merge. The threat of climate change to those seemingly mundane patches — which are seldom above water — is a threat to the entire oceanic ecosystem.

Indeed, the insidious impact of climate change on North Carolina’s coastal fisheries — the species in the water and the people who catch them, study them, sell them and eat them for dinner — may lie in murky meadows of submerged aquatic vegetation, or SAV.

The Unnoticed Foundation

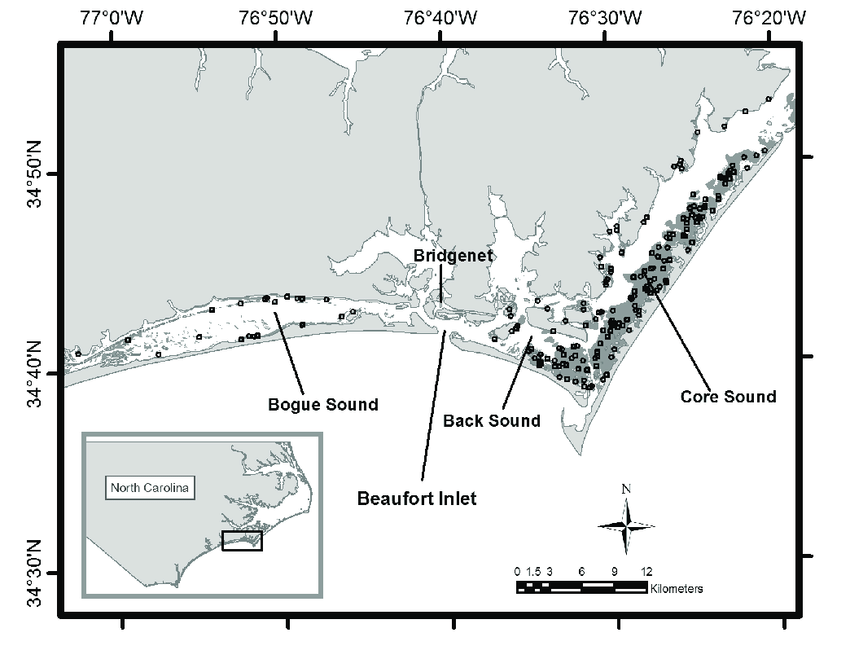

Kenworthy anchored his small vessel in Back Sound, between Shackleford Banks and the mainland of Carteret County. The east end of the sound is framed by two barrier islands, separated by a narrow inlet, which meet at a 90-degree angle at Cape Lookout. The junction forms what looks like the apex of a tensioned slingshot, ready to blast its ammunition inland.

“North Carolina is at this unique biogeographic boundary,” said Kenworthy, a thunderhead bulging over the Atlantic Ocean behind him. “There are probably only two or three places in the world like this, where major ocean current systems overlap and collide.”

From Corolla to Calabash, a confluence of tropical water from the Gulf Stream blends with a countercurrent of chilly sea transported on the Labrador Current from the North Atlantic, nourishing the grasses.

The unique mingling of seawater yields expansive meadows of both tropical and cold-temperate marine grass species that permit a year-round supply of vegetation supporting one of the world’s most diverse ocean habitats.

The ecosystem is a crucial variable to untangle not just how changing temperatures and rising sea levels will impact the grasses on which the scientist is standing, but how the marine organisms that live in North Carolina’s coastal waters — everything from microscopic critters to sharks — will respond to climate change.

A Better Understanding

Once regarded as a nuisance, ecologists now deem seagrass as vital to the health of coastal waters and communities. The vegetation absorbs excess nutrients, producing oxygen and capturing carbon dioxide. The grass also blunts the wave energy that erodes shorelines, slowing the persistent creep of barrier islands toward the coast. It also serves as a nursery habitat, providing food and shelter for a range of organisms.

Kenworthy, an adjunct faculty member at UNC Wilmington and a member of the scientific and technical advisory committee of the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, became fascinated with seagrass while growing up in coastal Rhode Island.

In the early 1900s, European scientists identified seagrass as an important component of coastal ecology. However, interest in its ecology languished for decades. “There were few people who really knew enough to care about seagrass,” Kenworthy said.

That is until the 1970s, when renewed interest intersected with a surge of research funds. Kenworthy was one of a handful of students funded by the National Science Foundation to study seagrass in the ’70s. At the time, little was known about its habitat and ecological function.

In the 1980s, as a member of a NOAA team, he helped create the first maps of seagrass habitat.

Based on those and more recent observations, North Carolina has somewhere between 100,000 and 130,000 acres of seagrass in addition to other SAV species that are equally important but harder to map, tucked behind the barrier islands and in estuaries up and down the Carolina coast.

In the ’80s and ’90s, experts began to notice that poor water quality was decimating seagrass in the Chesapeake Bay and along the Florida coast, but North Carolina was spared because of the high quality of its estuarine waters.

Color Wars

SAV, like an average front lawn, requires light to survive, making diminished water quality and higher sea levels its enemies.

“Think of a green, yellow, red scale bar to measure the quality of seagrass,” Kenworthy said. “We have a lot of yellow, a healthy amount of green and a few red. With climate change coming at us, all of our yellows will be red. Greens will become yellow because of things that are stressing the system.

“Nowhere are we seeing increases in seagrasses in North Carolina. That’s unacceptable.” And one thing is clear, Kenworthy said: “If you don’t have seagrass, you’re going to lose these fisheries.”

‘You can’t hide from a warming ocean’

Climate change affects creatures around the world. But land animals may have a slight advantage over marine species in running from the ill effects of global warming: the ability to escape.

While a fox can find shade in a grove or move to the north side of a ridge, a fish can’t hide from ocean warming.

As a result, said Rutgers University research ecologist Malin Pinsky, oceans and marine species are feeling the impacts of climate change because they are more sensitive to temperature change and respond faster than species on land.

“When I was starting my career, there was so much discussion about climate change impact on land, but there was very little discussion about the oceans,” he said.

“Because marine species are especially sensitive, we’re seeing responses in the ocean that are five times faster than what’s observed on land. You can’t hide from a warming ocean.”

A central question for scientists, including Pinsky, is how the transition will take place. “Climate variability and ocean warming are not abstract future problems,” Pinsky said. It’s here already, he said.

More evidence shows that ocean temperatures are increasing off the North Carolina coast, particularly in the winter, said Jim Morley, a scientist at East Carolina University’s Coastal Studies Institute.

Oceans serve as a giant heat sink for the globe. Without oceans, people on land would experience dramatically higher temperatures. The oceans absorb the majority of the excess heat. Because they distribute the heat widely, ocean temperature gains are subtle.

Nevertheless, even a small change in ocean temperature can have a profound impact on how marine species respond. For example, as an ocean warms, it loses oxygen, threatening the survival of species that require oxygen from the water. As ocean conditions alter, the likely result will be a massive rearrangement of marine life.

Some species may move north or south as ocean temperatures and currents are altered. Other species may thrive on the change to Carolina’s coastal waters, while still others are depleted. “With climate change, in North Carolina, there are going to be winners and losers,” Morley said.

Story courtesy of the FishingWire.com and coastalnewstoday.com