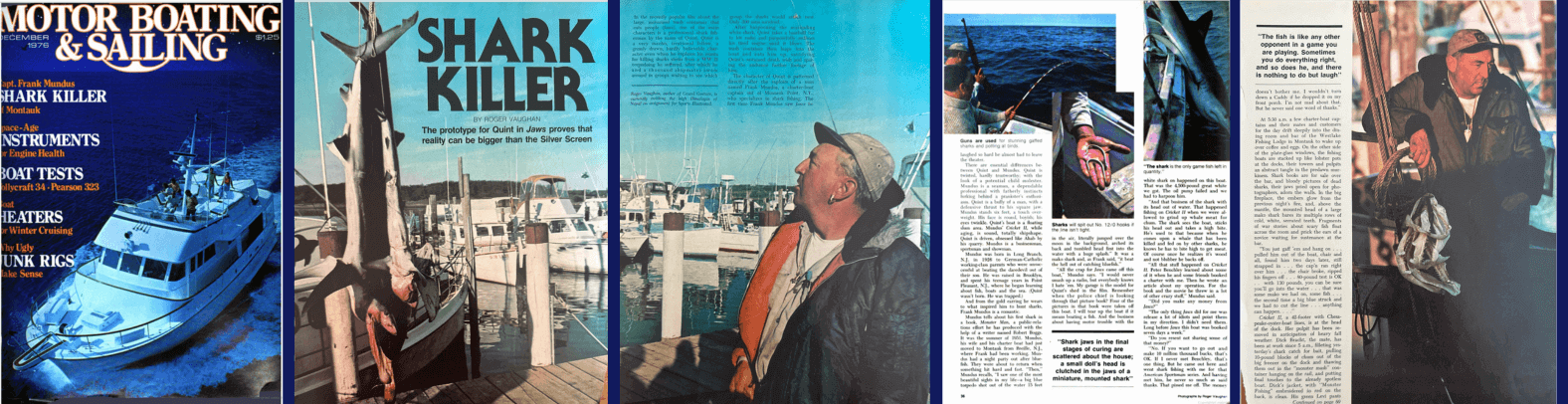

Shark Killer: Frank Mundus 1976

We’re republishing this article courtesy of writer Roger Vaughan, originally featured in the December 1976 issue of Motor Boating & Sailing. At the time, Jeff Hammond—co-founder of BoatTEST—was serving as the magazine’s Editor (1976–1979).

The prototype for Quint in Jaws proves that reality can be bigger than the Silver Screen

In the recently popular film about the large, motorized trash container that eats people (Jaws), one of the main characters is a professional shark fisherman by the name of Quint. Quint is a very macho, irrational fellow, a grossly drawn, hardly believable character even when he explains his mania for killing sharks stems from a WW II torpedoing he suffered, after which he and a thousand shipmates swam around in groups waiting to see which group the sharks would attack next. Only 300 men survived.

After harpooning the marauding white shark Quint takes a baseball bat to his radio and purposefully redlines his tired engine until it blows. The trash container then leaps into the boat and eats him up, satisfying Quint’s sustained death wish and sparing the audience further footage of him.

The character of Quint is patterned directly after the exploits of a man named Frank Mundus, a charter-boat captain out of Montauk Point, N.Y., who specializes in shark fishing. The first time Frank Mundus saw Jaws he laughed so hard he almost had to leave the theater.

There are essential differences between Quint and Mundus. Quint is twisted, hardly trustworthy; with the look of a potential child molester. Mundus is a seaman, a dependable professional with fatherly instincts lurking behind a prankster's enthusiasm. Quint is a bully of a man, with a defensive thrust to his square jaw. Mundus stands six feet, a notch overweight. His face is round, boyish; his eyes twinkle. Quint’s boat is a floating slum area. Mundus’ Cricket II, while aging, is sound, totally shipshape. Quint is driven, obsessed like Ahab by his quarry. Mundus is a businessman, sportsman and showman.

Mundus was born in Long Branch, N.J. in 1926 to German-Catholic working-class parents who were unsuccessful at beating the daredevil out of their son. He was raised in Brooklyn, and spent his teenage years in Point Pleasant, N.J., where he began learning about fish, boats and the sea. (Quint wasn’t born. He was trapped.) And from the gold earring he wears to what inspired him to hunt sharks, Frank Mundus is a romantic.

Mundus tells about his first shark in his book, Monster Man, a public-relations effort he has produced with the help of a writer named Robert Boyle. It was the summer of 1951. Mundus, his wife and his charter boat had just moved to Montauk from Brielle, N.J., where Frank had been working. Mundus had a night party out after bluefish. They were about to return when something hit hard and fast. “Then,” Mundus recalls, “I saw one of the most beautiful sights in my life—a big blue torpedo shot out of the water 15 feet in the air, literally jumped over the moon in the background, arched its back and tumbled head first into the water with a huge splash.” It was a mako shark and, as Frank said, “It beat the hell out of catching bluefish.”

“All the crap for Jaws came off this boat,” Mundus says. “I would never smash up a radio, but everybody knows I hate ‘em. My garage is the model for Quint’s shed in the film. Remember when the police chief is looking through that picture book? Four of the pictures in that book were taken off this boat. I will tear up the boat if it means boating a fish. And the business about having motor trouble with the whale shark on happened on this boat. That was the 4,500-pound great white we got. The oil pump failed and we had to harpoon him. “And that business of the shark with its head out of water. That happened fishing on Cricket II when we were allowed to grind up whale meat for chum. The shark sees the boat, sticks his head out and takes a high bite. He’s used to that because when he comes upon a whale that has been killed and fed on by other sharks, he knows he has to bite high to get meat. Of course once he realizes it’s wood and not blubber he backs off.

“All that stuff happened on Cricket II. Peter Benchley learned about some of it when he and some friends booked a charter with me. Then he wrote an article about my operation. For the book and the movie he threw in a lot of other crazy stuff.” Mundus said.

RV: “Did you make any money from Jaws?”

FM: “The only thing Jaws did for me was release a lot of idiots and point them in my direction. I didn’t need them. Long before Jaws this boat was booked seven days a week.”

RV: “Do you resent not sharing some of that money?”

FM: “No. If you want to go out and make 10 million thousand bucks, that’s OK. If I never met Benchley, that’s nothing. But he came out here and went shark fishing with me for True American Sportsman series. And having met him, he never so much as said thanks. That pissed me off. The money doesn’t bother me. I wouldn’t turn down a Caddy if he dropped it on my front porch. I’m not mad about that. But he never said one word of thanks.”

At 5:30 a.m. a few charter-boat captains and their mates and customers for the day drift sleepily into the dining room and bar of the Westlake Fishing Lodge in Montauk to wake up over coffee and eggs. On the other side of the plate-glass windows, the fishing boats are stacked up like lobster pots at the docks, their towers and pulpits an abstract tangle in the predawn murkiness. Shark books are for sale over the bar, and bloody pictures of dead sharks, their jaws pried open for photographers, adorn the walls. In the big fireplace, the embers glow from the previous night’s fire, and, above the mantle, the mounted head of a large mako shark bares its multiple rows of cold, white, serrated teeth. Fragments of war stories about scary fish float across the room and prick the ears of a novice waiting for sustenance at the bar.

“You just gaff ’em and hang on . . . pulled him out of the boat, chair and all, found him two days later, still strapped in . . . the cap’n ran right over him . . . the chair broke, ripped his fingers off . . . 80-pound test is OK with 130 pounds, you can be sure you’ll go into the water . . . that was some mako we had on, some fish . . . the second time a big blue struck and we had to cut the line . . . anything can happen. . . .”

Cricket II, a 42-footer with Chesapeake-oyster-boat lines, is at the head of the dock. Her pilothouse has been removed in anticipation of heavy fall weather. Dick Brackett, the mate, has been at work since 5 a.m., filleting yesterday’s shark catch for bait, pulling 10-pound blocks of chum out of the big freezer on the dock and thawing them out in the “monster maw” container hanging on the rail, and putting final touches to the already spotless boat. Dick’s jacket, with “Monster Fishing” embroidered in red on the back, is clean. His green Levi pants are are creased, his topsider moccasins are as white as the chunks of shark meat in the bait buckets.

Frank shows up at 6:30 lugging boots, a quilted coverall suit and a briefcase. The day’s party is late, so Frank quickly goes to work separating the meat from a set of jaws he removed from a shark the day before. A photographer takes pictures. “I hope with this northerly breeze you got on the green filter,” Frank advises. He works with a surgeon’s skill on the cold, slippery jaws, sometimes holding the razor-sharp, tapered Normark knife with two fingers. “If the knife don’t get you, the teeth will,” Frank says, but a quick count shows he still has ten fingers.

“These jaws are a sideline,” Mundus says, “like the jewelry.” He reaches carefully inside his jacket with a clean finger and pulls out a gold chain. A shark tooth the size of a half dollar flops out. It’s gold and platinum setting is weighty. The sapphire set in the gold radiate the morning sun. Frank says the stone alone are worth $500.

“How much do you get for a jaw?”

“It depends on a person’s approach.” If he says ‘I want,’ maybe $100. ‘Do you have?’, the price goes down. ‘I’m interested,’ it’s even less. Like the jewelry. It’s $75 to the fishermen, $100 to the tourists.” Frank smiles like a TV detective. “You got to have heart in this business.”

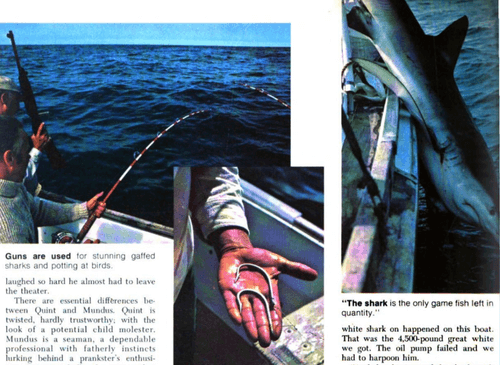

The party shows up, six fellows in their early 20s with six hangovers and four guns: two shotguns, a rifle and a police .38 handgun. Frank’s all-purpose word for the people who charter his boat—idiots—seems appropriate this morning. There’s another guy, Bill Wilson, a photographer of birds, who Frank sometimes accommodates. Wilson and the guns seem a strange match-up. There are also guns in a rack below, and word is that they are used for more than stunning gaffed fish. Mundus simply likes to kill things, someone told me when he heard I was headed for Montauk. Wilson receives my quizzical look. “Frankly,” he says, “I expected some abuse from Mundus if he thought I was around interested in bird photos. Surprise. He has been great. He’ll shoot a herring gull or a black and white petrel. There is an abundance of both birds. But out there he is only concerned on all other birds, and no one better take a shot at one.”

Two-and-a-half hours south of Montauk Point, three of the six hangovers have lingered into seasickness. Frank takes a Loran bearing, checks the engine, and circles slowly, estimating drift and beam-to-drift, rocking 10° or more in the swells. It will be a long day for the sickies. Dick selects three rods custom-made by Johnny’s Tackle Shop in Montauk from the 16 rigs on board. Fifteen-foot wire leaders are attached to 50-pound test. Number 12/0 hooks hold bait fish (whiting is the favorite) and shark fillet. Frank strips line off the Everoll Italian reels. He rigs a deep line 200 feet out, a medium line and one fairly near the surface with a cork. Dick throws the first ladle of chum over the side followed by a chunk of shark meat. A slick appears on the surface to windward.

“OK, destructions,” Mundus says, eyeing the three mobile members of the party, who have already unpacked their guns. “Hang on. That’s it.” There is nervous laughter from the kids. Frank gives them a stare, then chuckles. This is the captain speaking, for certain.“If it’s a normal pickup the line will snap out of the clothespin and go out, and we’ll give the fish a proper drop back.” The words blur together in Mundus’ nasal monotone. “One of you should be galloping in our direction at that point. We’ll jam the pole into your waist holder and you should wind slack. The reels are almost idiot-proof. Lever up frees the spool; down, it’s in gear. If it’s a fast pickup, we just jam it in gear and hang on. If the fish stops and runs toward you, don’t say the famous last words, ‘Oh s---.’ Just keep winding because if you don’t he’ll spit the hook. Keep the line tight and we’ll tell you the five thousand things to do, one at a time. If you have any questions don’t ask until we get a fish on the line.

“If you are going to shoot, do it from the stern quarter and that’s all. You either came out here to fish or shoot.” We wait and we rock. Frank cleans jaws; a process, he says, that can only be done with a knife. The jaws are cartilage. Bigger and softer the older they will be left. Surgery is the only way. Then a saltwater soak, a peroxide bath, and sunlight, all in classified amounts, and the jaws end up a gaping, symmetrical, ghostly white. “Pickup!” The reel of the deep line whirrs. Frank moves with amazing quickness. He rods, throws the gear lever and waits for the young angler to get set. It’s a small shark. Even so, the angler fights to hang on and tires quickly. In five minutes a small brown shark is brought to the boat. The fish is about 75 pounds, and too small. Mundus decides to tag and release it. The tag is a short plastic tube containing a number, with a barbed plate on one end. Frank attaches the plate to a small harpoon and thrusts the plate into the shark’s back. Blood flows, but there is no other reaction from the fish. Dick cuts the wire, and the fish disappears.

Frank says he doesn’t think sharks can feel pain. He recalls trying to chase a bunch of blue sharks away from the boat one time with a bayonet tied to a pole. “I jammed it into one fish and it came out the other side. No reaction. No thrashing.”

“We’ve had archers on board—we’ve had ’em all—and when the arrow hit the fish there was no reaction until the fish came to the end of the leader and felt tension. I think the restriction, not the pain, is what makes them fight. We finally got rid of the blues by lashing a hook and tying a can to the leader. They would take the bait, then try and get away from the drag of the can. Just like a dog with a can on its tail.”

Ammo being burned up on the stern. A few gulls have come around to check out the food situation, and the boys are banging away. They aren’t much of a threat. Not many people can hit a moving target from the deck of a rolling boat. For all their effort only one gull is belly up. The rattle of the .38 is making a hell of a racket, which Dick says is good for the fishing. Sharks like noise.

Frank’s friend Harry, a diesel-injector repair specialist who fishes for sharks with great expertise, hangs a big bar of pogrom off a kite Frank keeps for fishing the lee side of the boat. The gunners react like kids at an amusement park.

“Pickup!” It’s the deep line again, a decent fish. Dick handles the rod, sets up the next angler, one of the sick ones who has lurched out of his bunk, sallow-faced by his crack at a shark. “I’ll hunt this guy,” Frank says, peering into his face as he struggles against the fish. “His sunglasses aren’t even tightened up yet. You’re not doing right. Wow, don’t let it go slack. Look at the reel when you pump. Come up slow, and go down fast while you wind. I’ll be back in half an hour to see how you’re doing.” Mundus says it acts like a mako, a decent fish. “Decent” in Cricket II language means something worth taking: maybe 200 pounds or more. “From the feel he’s been boiling, he’s wrapped up in the line. Watch that slack! See, look at the line come up, he’s going to jump, get ready . . .

One hundred feet astern there is a great churning of water as the fish breaks the surface, unable to jump clear because of the wire leader wrapped around him, but showing us his might as he froths the sea. The befuddled angler lets the line go slack again, and suddenly the fish is gone. Frank expresses consternation lightly, with good humor. He has seen too many idiots lose good fish to let it bother him. The breeze has freshened during the day, and the trip home is rough. “Every year it gets harder,” Mundus says, steering from the flying bridge, hanging on as Cricket II rolls through the beam seas. “A few years ago we went an hour off the Point. Now we go out a mile and a half. But there used to be a lot of buffalo on the plains, too, and deer on Montauk. There are too many humans. We ought to have open season on them.

“Five years ago you couldn’t find another boat to go shark fishing. There were plenty of school tuna, white marlin, swordfish. Shark is the only game fish left in quantity. It’s a poor man’s hobby. No need to go to Acapulco, you catch ’em here.” But the shark population is dwindling. The long-liners have hurt all the game fish. They set a 20-mile line with 2,000 hooks. They only take the market fish, so giant tuna, sharks, white marlin are cut loose dead. One long-liner can kill 500 sharks a night with no problem.

“That mako, it was nice to have a shot, but it would have been nicer to catch him. That kid who had him on, he didn’t know. Typical American youth. ‘Hey man, far out.’ Maybe someday he’ll realize what he had going and kick his ass.” Frank gives Dick the wheel and goes to the deck, where one of the kids asks him how that mako shook the hook. “You saw him do it,” Frank says. “Yeh, but how?” the kid wants to know. “Well,” Frank says quietly, as if to begin a serious explanation, then turns toward the ocean and screams: “HEY! HOW’D YOU DO THAT?”

From the dock it’s a dash to the market before it closes. Frank’s choice fish is stowed in second. The length of poly rope on the front bumper is left over from when the van was stuck in surf. Mundus rigged the poly around the bumper to the driver’s seat to switch gears. “Then everything failed,” Frank says. “We had to keep it in gear. On the highway, the driver’s side door keeps flying open. ‘Don’t worry, mister, happens all the time,’” Mundus mutters to a startled oncoming motorist.

Frank’s house is in the dusty disarray of a man recently divorced who works from 6 a.m. until nearly 7 p.m. seven days a week. Shark jaws in the final stages of curing are scattered on tables and window ledges to catch the sun. Mail covers the kitchen table. The bulletin board over the table is a crammed montage of pictures, clips and personal delights. A small doll’s head is clutched in the jaws of a miniature, mounted shark. There are pictures of Frank in younger days. With the sweat-stained, broad-brimmed hat he affected, his dark complexion and black-eyed, crooked smile, he resembles a young Robert Mitchum. Mundus has lost some muscle tone, and a small paunch he made with his heart this summer has curtailed his drinking, but swashbuckling is still his natural bent. His wide leather belt is hitched with the bronze barb from a harpoon. The huge shark tooth gleams from around his neck, and his earring, now studded with diamond chips, was formerly his wedding band. He seems pleased with the new freedom his divorce has afforded. “I’m on my own after all these years, and it’s a nice feeling. So, I make decisions for me. I’m 50. I trade it to the halfway mark, one quarter of a bicentennial.”

“You won’t take that.”

“I ain’t worried, and a lot of people will be happy.”

The Montauk charter fleet has never been enthusiastic about Frank Mundus. First, he’s a loner. “Always will be,” Mundus says. “When I first come up here, the old-timers thought the new boy should bow down. I didn’t. Then I was a shark boat. No one sent me overflow business. They told people I didn’t know how to fish anything else. It was something I had to live down, like a black boy in a white school. He has to be better at everything to make it.”

Success didn’t help Frank’s local status, and his belief that bad press brought more business than no press at all didn’t help him win friends. And there were the jokes. One customer liked a good prank as much as he admired the one he once played, as he found a willing accomplice in Mundus. One year they brought back a mermaid from offshore, topless, with a costume-shop tail. They toured the waterfront with her before dropping her on the dock with the hoist. The next year it was the mysterious box. Frank sent a runner to all the docks with a rumor so when Cricket II landed a big crowd was waiting. There was audio wired underneath the box, which was old and weed-covered. Dick’s hand was bandaged. They told the crowd he got burned from just touching the box. When it was pried open, Frank’s customer emerged in a monster suit and scared people half to death.

When weather closed out most boats, Frank would refund his party’s money, pick out a salty bunch wearing oilskins who had been canceled by another boat, and take them fishing. “We hold up a wrecking bar. If it bends, we don’t go out,” Mundus says. He just wouldn’t play the game.

Mundus played his game, which is fishing, and did well enough to make it on his own. He and Cricket II won the Point Judith Tuna Tournament in 1962, which is a world series of sorts. Then, in 1964, Mundus caught the biggest great white, to date the largest great white ever: 17½ feet long, weighing 4,500 pounds.

“When we first came across white there was no one to ask how to, who, or what,” Mundus says. “We had to play it by ear. We lost a lot of them until we perfected the method. Yo know when a great white is around because he comes to the boat. You set to him. I figure we have 15 minutes to prepare the live rig 130-pound test rig. Otherwise he will get bored and leave. We hope to catch a bite first. If the white comes, we put two entire blue fish fillets on the hook. The blue has to be fresh. Bad shark meat makes excellent shark repellent.”

Mundus had engine trouble and had to harpoon his great white, a fact he still suffers. His may be the biggest but it wasn’t caught on rod and reel and therefore isn’t a record. But it must have been an ultimate thrill.

“Yes and no,” Mundus says. “We killed him. It was a struggle. Then you see him lying on the beach and you wonder. It took him a lot of years to get that big. Then here comes a human and kills him with modern machinery. I felt sorry. Everybody said hooray but I felt sorry.”

“The fish is like any other opponent in a game you are playing. Today mako, I mentally tip my hat to that fish. Sometimes you do everything right, and so does he, and there’s nothing to do but put your pole down and laugh. Frank brought a shark weighing about 2,500 pounds, a white, for a hour and a half one day. It was Harry’s fish of a lifetime, more than twice the weight of the one he caught a few years ago. On the way home he said he was happy just t’ have had a crack at him.”

It is blowing hard out of the northeast at 6 a.m., but Cricket II is once again heading for the deep water frequented by sharks. The boat handles well in the sloppy going. Her motion is solid. She has very little bounce. She feels heavy. Her 6-71 Detroit Diesel turns a 24x18 wheel through a 1½-to-1 reduction on a two-inch shaft. She puts her head down like a good fullback and grinds it out at 15 knots.

Mundus says the boat is heavy. Cricket II was built by a man named Cockrell at the Glebe Point Boat Company in Burgess, Va. Mr. Cockrell had never been on the ocean. When Frank asked him to build a sea boat, Cockrell said he couldn’t. The heaviest planking he had was two inches. Frank assured him that would do it. Cockrell told Frank to draw him some lines on a window shade. Mundus did and brought the shade to Virginia. Cockrell tried to increase the length two feet because he had two “sticks” that length, and he hated to cut two feet off them. Four months later Cockrell called and said to come get the boat. The frames are 3x3 sawed oak. The keelson is the heart of a single pine tree, 10x12. The garboard “sticks” are 12x2 by 42 feet. The stem is 14 inches thick. Frank says he hit a buoy one night dead on at speed and the only damage was a fist-sized chunk knocked out of the stem. The hull, decks and deckhouse cost Mundus $4,000 in 1946. He didn’t discover until a few years ago that the port rail was three inches lower than the starboard rail.

Today’s party is small, three men in their 30s who are serious about catching sharks. Only one of them remains upright when Mundus cuts the engine, 25 miles offshore. Today the boat must be rocking through 15°. We are dunking the after spray rail. It’s a job just hanging on. Frank rigs the lines and we wait. And we wait. Once every minute a ladle of chum splatters like vomit into the water, followed by the plop of a meat chunk. Gulls appear. Frank and Dick drag out their guns and shoot a few to break the monotony. Frank is a good shot. Balanced on the crazily pitching deck, he hits three birds with a dozen rounds, which is good enough to win a batting championship. The customers take a few shots before the gulls leave. “Shoot at the cork,” Dick says. “The noise might help.” Mundus goes below, opens his briefcase and braces himself against the chart table to answer mail. Even with the price going up to $350 a day, reservations for next season are coming fast. Two hours and no fish. Sharks are like cops. You can never find one when you want one. Frank comes on deck, walks to the stern and yells over the water, “Come on! This is serious!”

Thirty minutes later a fish hits. Blue shark. “Pull with your back and keep your head straight,” Frank tells the first angler. “Your brains don’t weigh beans.” It’s a 150-pound fish and we keep him. The fisherman wants to know if he’s a big one. “They don’t come bigger in that size,” Frank assures him. The line is barely rebaited before a second blue hits. At 250 pounds, we keep him too. Shark fishermen are trophy hunters, after all. They want pictures, if not the heads. And Frank wants the jaws. We take three blues in all. The morning’s weather has abated. The sun has come out; the sea is calm. It’s a peaceful trip home under a clear September sky.

Talk on the bridge turns to a favorite subject: idiots Frank and Dick have known. They recall an American Sportsman cameraman who was shooting film from a shark cage. The day after a brown shark stuck his nose in the cage, the guy complained the smell of chum made him sick. “He smelled it through a face mask and mouthpiece,” Frank said, with his best Mitchum sneer. Then Frank remembers another shark cage, and a fellow named Peter Gimble, who starred in Blue Water, White Death, a spectacular documentary film about sharks. “Peter worked six years with us developing his cage from an old one he found in my yard,” Mundus says. “Finally he got it just right, and we started working with it. One day he brought two other divers out with him. I knew what he was going to ask before he asked. He wanted the other two guys inside, and he would be outside with the shark. I told him we’d try it with just one small shark at first. A small blue came along, and Peter flopped into the water. The blue swam over to him and he grabbed its nose, turned the fish, and shoved it in another direction with the tail. After that he began banging them in the nose with his camera. We also discovered a bullet fired in front of the shark’s nose would turn the animal.

“Naturally Gimble began swimming with several sharks. One day I counted six browns, a tiger, five or six duskies and two makos. When Peter broke the surface that was the dangerous point, because he couldn’t see. I was on the pulpit with a rifle. Peter stuck his head back in the water and saw the blue coming at him. But he didn’t see the blue on his right, or the blue coming from behind him. He hit the fish in front with his camera as I fired between his tanks and the blue behind him. He heard the bullet, turned right and smacked the one on the right. It was close.”

“Is Gimble brave, or stupid?” I wanted to know. “Neither. He’s smart. He asks questions. He takes advice. He figures angles. It was gratifying to sit in the audience and watch him do stuff we worked out together in that film.” “How about you, Frank? Have you ever been scared?” “No. Maybe I’m too stupid to be scared. What is there to be scared about? My old man was standing bow watch during a storm one night on board the carrier Langley, during World War II. A wave washed him overboard. Two or three waves later, he was washed back on the stern. He said anyone who was born to hang isn’t going to drown.”

On the dock the weighing and photographing ritual unfolds. Mundus handles the hoist while Dick checks the scales. The customers take turns with the camera and the fish. Dick cuts them a big fillet to take home to horrify the neighbors. A tourist asks Mundus what kind of sharks he’s got. “Dead ones,” Frank tells him, and takes off in his van, slamming the door several times as he bounces across the parking lot.

About the Author:

Roger Vaughan is an internationally published journalist and writer. With 23 books to his credit, and a variety of other work that includes a major film, a play, a musical pageant, and scores of magazine articles, videos, and internet reports, Vaughan’s major interest is writing about individuals who have had a strong influence on our culture.

As youth and education editor at LIFE magazine, Vaughan covered Bob Dylan’s European tour, the Beatles, the Monterrey Pop and Woodstock music festivals, the Haight-Ashbury Summer of Love, Andy Warhol’s Factory, the youth movement, the arrival of LSD, and Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony’s tour of China. Among other notables he has written about are Walter Cronkite, Roy Disney, Rod and Olin Stephens, Malcolm Forbes, Tony Gwynn, HRH Princess Margaret, Ann Sophie Mutter, Lee Marvin, and Mstislav Rostropovich. He was founding editor of TheYACHT magazine.

Vaughan has written two books about the America's Cup, and has contributed to several others. He has written biographies of media magnate Ted Turner, music director Herbert von Karajan, medical researcher Dr. Hillary Koprowski, educator/philanthropist Harry Anderson, and Victor Kovalenko, head coach of the Australian Olympic Sailing Team. His biography of Arthur Curtiss James was published in March 2019. His biography of Patsy Bolling was published in January 2025.