Taking Care of PYI’s PSS Dripless Shaft Seal

Advocates of dripless shaft seals are quick to point out their benefits over conventional stuffing boxes (no leaks, no flax to replace, no shaft scoring) but the zinger is always the same — “they’re maintenance free.” While it’s true dripless shaft seals such as PYI’s popular Packless Sealing System (PSS) require less care than a traditional packing gland, nothing on a boat is truly maintenance free. Let’s take a look at maintaining and troubleshooting these modern marvels.

Dripless Shaft Seal Background

There are two primary types of dripless shaft seals — lip seals and face seals. Lip seal units employ a synthetic rubber sleeve encased within a metal housing. The seal fits snugly against the shaft to prevent water entry and remains stationary with the shaft rotating inside it.

Lip seal units are less expensive than face-seal models and while they have a fair amount of tolerance to shaft misalignment and vibration, they have disadvantages as well. The constant contact between the rubber seal and rotating shaft means the seal will eventually wear out and that some shaft wear will likely occur in the process. Installation-wise, shafts that are not free of corrosion, nicks, pitting, etc., may be difficult (if not impossible) to retrofit with a lip seal unit.

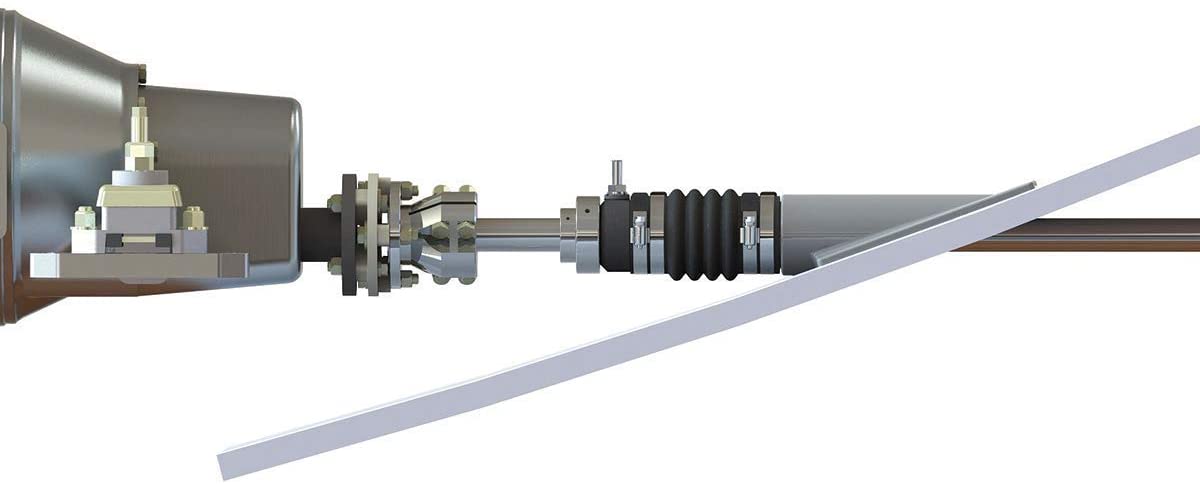

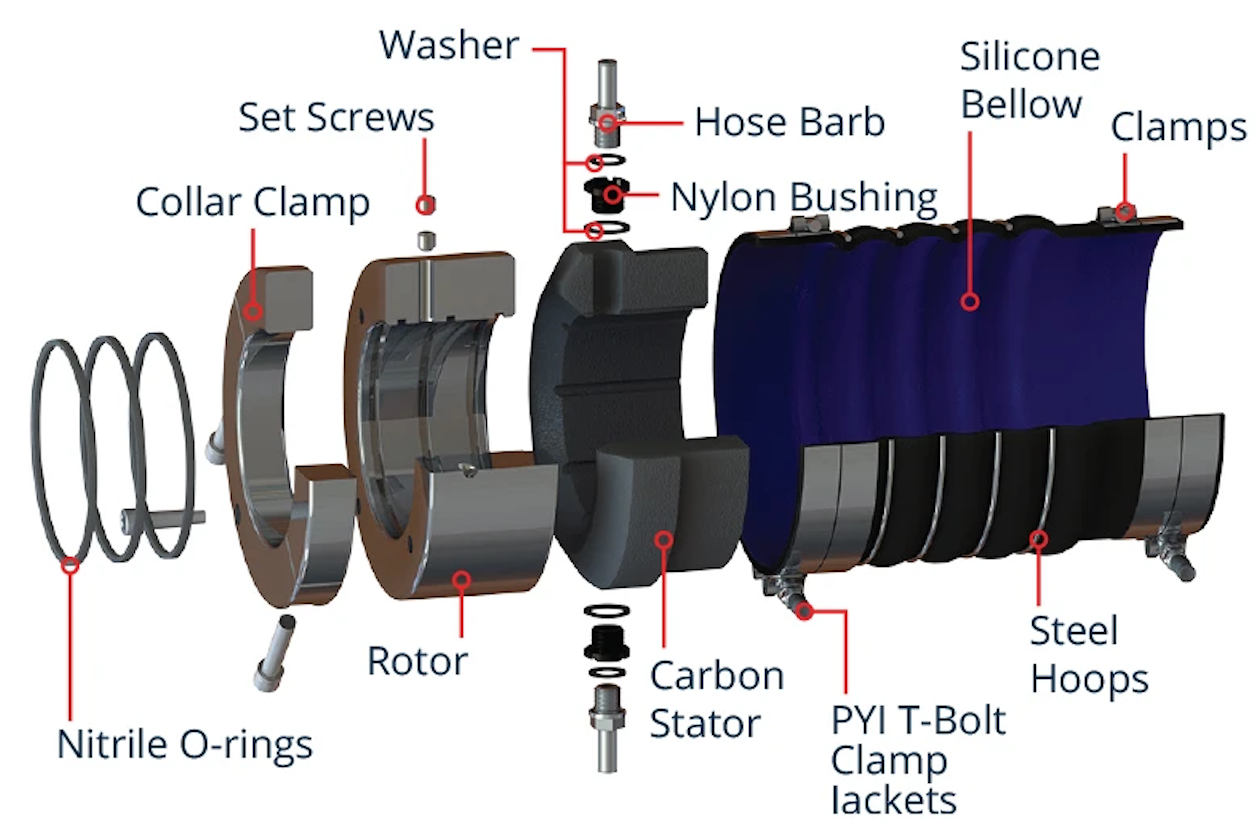

Face-seal units like the PSS form a mechanical seal and work on the principal that when two highly polished surfaces are properly mated water can’t pass between them, even when one is spinning and the other is stationary.

The static surface of the PSS seal is a high-density, carbon-graphite flange held in contact against a stainless-steel rotor that is attached to and turns with the shaft. The flange is attached to the shaft log by a flexible nitrile rubber bellow. Water pressure (and resistance of the bellow to compression) maintains pressure to keep the faces of the flange and rotor together.

In addition to the rotor, flange, and bellow, the PSS unit also contains two Nitrile O-rings (used to seal the rotor to the shaft), four stainless steel set screws (to secure the rotor to the shaft) and four stainless-steel hose clamps used to attach the rubber bellows to the shaft log and carbon-graphite flange.

Maintenance

As with any rubber hose used below the waterline, the bellow must be inspected regularly for signs of cracks, wear, aging or chemical deterioration. PYI recommends the bellow be inspected twice annually and replaced every six years regardless of condition, at which time it also recommends the O-rings and set screws in the stainless-steel rotor be replaced as well.

Bellows that are located in the same space as non-sealed batteries may require more frequent replacement due to battery off-gassing while charging. Sulfuric acid vapors (as well as use of an ozone machine) will accelerate deterioration of the rubber bellows. PYI offers a PSS maintenance kit that contains a bellow, two O-rings, five set screws, four hose clamps and an Allen key.

Finally, if a whitish deposit is noticed around the edges of the rotor and flange, the residue is actually salt crystals that form in saltwater anyway. The salt won’t harm the unit and can be easily removed with a damp cloth.

Troubleshooting

In a nutshell, a PSS seal should never leak at rest and while underway should never make noises or generate more than a fine spray or mist. Let’s explore the various problem scenarios you could experience, their causes, and how to correct them.

•Scenario number one: Your boat is docked and the engine is not running, however while checking the engine compartment you notice water leaking from the shaft seal.

Because there are a couple of areas that could be responsible, the first step is to thoroughly inspect the seal to determine where the leak originates. If leaks are sighted where the bellows attaches to the shaft log or carbon graphite flange, check the hose clamps for looseness or damage. If leaking around the nylon hose barb, check that the hose clamps (and barb itself) are snug and properly tightened.

The most common cause of minor leaking is the presence of foreign material between the stainless-steel rotor and carbon flange — even a single grain of sand or blade of grass can break the seal, resulting in drips and leaks. To clean the mating surfaces of the rotor and flange without disassembly, simply compress the bellows while forcing them apart, allowing the incoming water to flush the debris out. You can also wipe both mating surfaces with clean cloth while flushing, just be quick about it as water will be gushing into the boat while the bellows is relaxed.

•Scenario number two: Still tied to the dock, you’ve cleaned and flushed the two surfaces to remove any debris, however water is still leaking between the rotor and graphite flange.

The next step is checking the bellows for proper tension. Even when installed correctly, the bellows can lose tension over time due to slippage at the shaft log, particularly if the log is smooth and lacks a stop or area where the end of the bellows can butt up against. Conversely, it could be the rotor moving up the shaft (due to excessive vibration) causing the bellows to lose tension.

After determining whether the problem is with the bellows or rotor movement, loosen the rotor and recompress the bellows per the installation instructions. While adjusting the bellows, remember that the numbers given in the bellows compression chart are average figures and provided as a guide only – the exact compression amount required to provide a good seal can vary between installations due to number of reasons, from differences in engine mounts to variations in cooling water pressure provided to the seal. As such, you may need to add an additional ¼” (6.35 mm) of compression to attain proper compression.

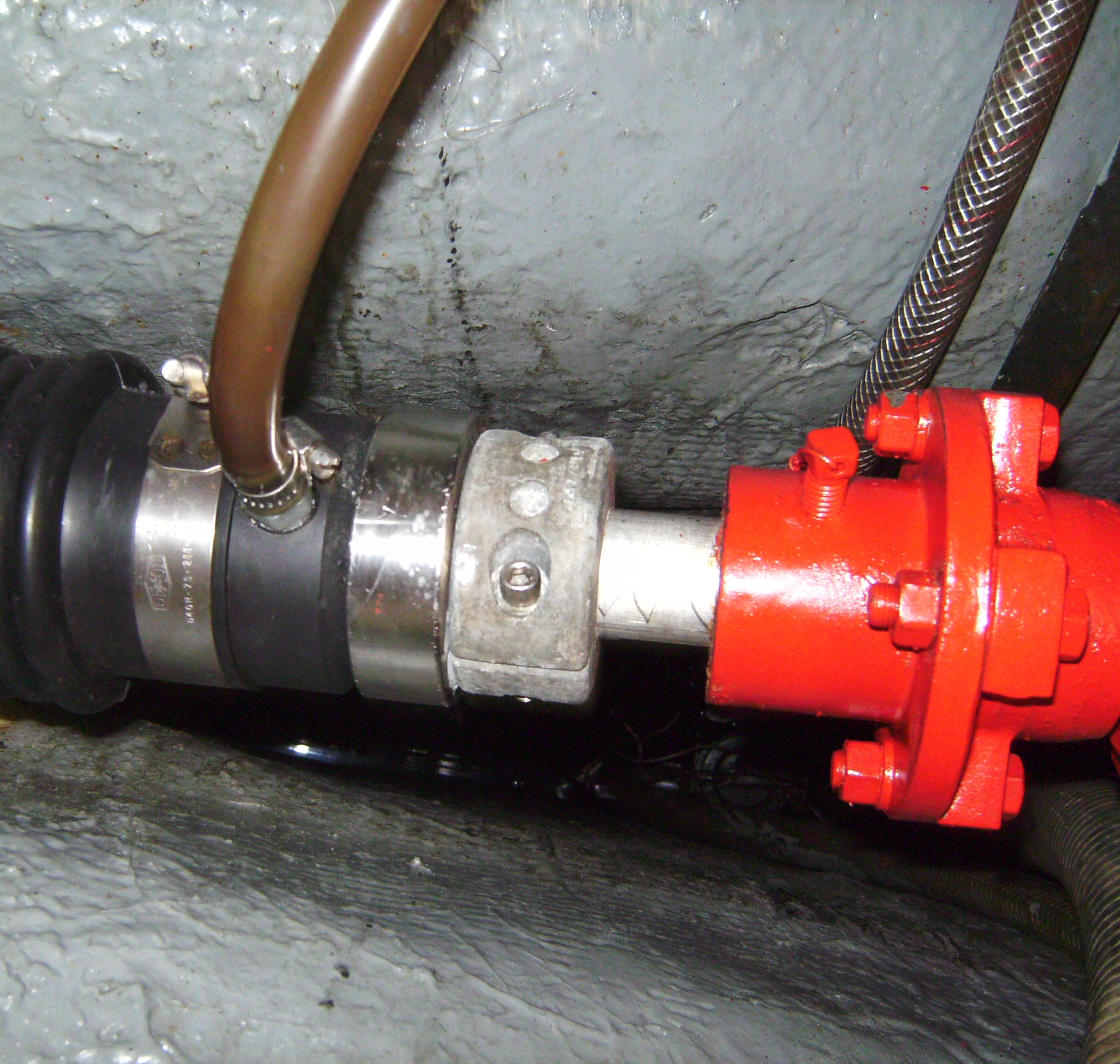

As a final belt-and-suspenders approach, installation of a collar zinc inboard of the rotor provides an additional layer of insurance to keep the rotor in place, particularly if movement due to excessive vibration is a concern.

•Scenario number three: While underway and operating at cruising rpm, there’s a fine black mist emanating from the shaft seal.

This is part of the break-in period mentioned in the installation instructions. The carbon flange is polishing the stainless-steel rotor, a process that generates a fine mist that’s often accompanied by black dust. This is a normal occurrence and should stop after the first hour or so of operation, however if it continues past the break-in period, a captain will want to determine why.

One possibility is incorrect tension of the bellows (which can be corrected as discussed above) however another possibility is the presence of foreign material on the seal faces. Although most contaminates can be flushed or wiped clean, some may require more aggressive removal methods. In this case, polish the seal using a folded piece of 600 grit wet/dry sandpaper. This can be done while the boat is in the water by compressing the bellows slightly, placing the sandpaper between the faces and making 8 to 10 sweeps around the seal.

If the vessel is hauled, take this one step further by polishing the mating surfaces with toothpaste (those containing baking soda work best). Loosen and slide the rotor forward on the shaft, apply a thin, even coat of toothpaste to the carbon flange, then press the rotor against the flange while turning in order to polish both surfaces. Wipe both surfaces with a clean, soft cloth and acetone prior to reassembly.

•Scenario number four: The seal is drip-free at the dock, but sprays water while underway.

As with the previous scenario, contamination of the seal faces (this time with oil or grease) is the likely cause. The PSS instructions caution against using silicone or petroleum-based products during installation of the unit. A single drop of oil or speck of grease on the seal mating surfaces can result in water spraying from the seal while underway. Cleaning the seal as described in scenario three should correct the problem. Keeping other fluids (antifreeze for example) away from the seal will also help prevent contamination problems.

•Scenario number five: While cruising towards a favorite anchorage, there’s a high-pitched squeal coming from the seal.

Immediately reduce speed and if possible, come to a complete stop and shut down the engine. Sudden squealing generally occurs in powerboat installations due to overheating caused by lack of cooling water. A dry running seal can get extremely hot, so avoid the natural tendency to touch the unit in efforts to verify overheating. Instead, check for the smell of burning rubber, use a non-contact thermometer (if handy) or simply inspect the unit once cooled.

If this is a new installation and the vessel runs faster than 12 knots or so, check to make sure cooling water was plumbed to the seal via the nylon hose barb fitting. If not, once the boat exceeds 12 knots, a vacuum can form at the stern tube, drawing cooling water away from the seal and causing it to overheat.

If the seal is plumbed correctly, check the hose for kinks or damage. The steps for this inspection will depend on how the unit is plumbed into the engine cooling system or a thru-hull, but may involve pulling the hose at the nylon barb at some point to verify the presence of cooling water.

It’s not unheard of for the hose or nylon fitting itself to become clogged with debris or even ice in colder climes, one reason why some surveyors recommend blowing out the hose (or simply replacing it) annually as part of normal preventative maintenance.

Slower moving displacement vessels can also experience overheating, particularly with an older PSS installed. All new units have the nylon hose barb mentioned above, which is either plumbed to provide cooling water to the unit or (in the case of slower craft) used as a vent tube for the bellows. Older seals may not have this vent, requiring you to “burp” the unit of air by decompressing the bellows each time the vessel is launched. Failure to remove this air pocket can prevent cooling water from reaching the seal, causing it to overheat.

Should overheating occur, check the seal thoroughly as soon as possible and replace any damaged components prior to placing the vessel back into full service.

By Capt. Frank Lanier

Captain Frank Lanier is a SAMS® Accredited Marine Surveyor with over 40 years of experience in the marine and diving industry. He’s also an author, public speaker, and multiple award-winning journalist whose articles on seamanship, marine electronics, vessel maintenance and consumer reports appear regularly in numerous marine publications worldwide. He can be reached via his website at www.captfklanier.com.