Tech Talk - Boat Fires – Prevention, Suppression, Detection & Preparedness

First – the good news: Boat fires are rare. Out of the 4,588 boat accidents listed in the U.S. Coast Guard’s 2011 Recreational Boating Statistics report, only 218 involved some kind of fire or explosion. Now consider that there were nearly 12.2 million registered boats in the U.S. in 2011, which made the chances of experiencing a boat fire less than .002 percent. Next add in the fact that diesel fueled boats are less likely to suffer from a fire or explosion than a gasoline powered boat. The final picture is that, statistically speaking, the chances of suffering a boat fire or explosion on a Nordhavn are exceedingly small.

Then there’s the bad news: When they do happen, boat fires are very dangerous – particularly so for trawlers that spend much of their time far from help. It’s one thing to jump overboard and swim to shore or be picked up by a fellow boater in a small lake, it’s quite another to be 1,500 miles offshore and abandon ship because your boat is on fire.

So, while it’s comforting to know they’re rare, the ever-present danger of boat fires demands vigilance on the part of both the boat builder and the boat owner. The builder can work to build in robust fire prevention, suppression and detection systems to mitigate the danger, and the owner can stay alert and be prepared to take action if necessary.

Prevention

One might think the main job of an engineer or designer is to simply make things work. Engines have to burn fuel to turn propellers, wires have to conduct electricity all around the boat, and appliances have to deliver an expected level of convenience and comfort. I would add another line to the task of the engineer or designer: Make things work without catching on fire!

Fuel is combustible, engines generate gobs of heat, and electricity can cause sparks and melt metal in an instant if the wrong wires get crossed. Still, we need the fuel, engines and electricity to make the boat move through the water, to generate electricity and to power lights, pumps, TVs and other devices. And on a Nordhavn everything has to work while being subjected to the continuous vibration, flex and stress of spending days, weeks or months out on the open ocean.

Thankfully there is a wide body of knowledge, standards and practices aimed at building a boat so it will work as desired without turning into a Roman candle. If you look at the American Boat & Yacht Council (ABYC) rule book, for example, you’ll see that the section for electrical installations dwarfs the other sections – largely due to all the guidance on how to design and install an electrical system so it will not start a fire.

Wire size, circuit protection placement, and insulation ratings just begin to scratch the surface of all the preventative measures that are called for. This makes good sense when you look at just how many fires are caused by electrical issues.

Boat U.S. – the AAA of the boating world – did some research a while back to determine the most common causes of boat fires by digging through piles of insurance claims. More than half of the fires investigated (55%) were found to have been caused by wiring and electrical problems, with wire chafing found as the most common problem.

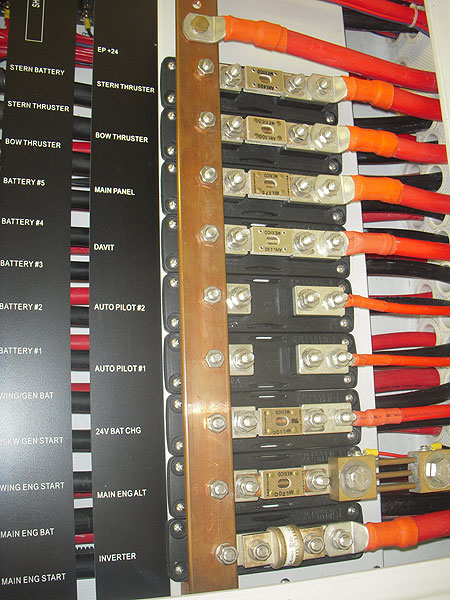

Chafing is one of those problems of scale. The bigger the boat, the more wires there are, and the greater potential there is for chafing issues. A single Nordhavn can contain a 120/240V alternating current system in addition to 24V and 12V direct current systems, all of which comprise hundreds and sometimes thousands of electrical circuits. Proper cable installation and robust chafing protection is just one area where builders and installers have to stay focused to ensure they’re not creating a situation that could start a fire.

However, over the lifetime of a boat – which can be decades for a Nordhavn – electrical faults, equipment malfunction and even lightning strikes can conspire to start a fire. This is another reason why layer upon layer of fire prevention is designed and built into the original electrical system. Marine-grade cable with robust insulation made to withstand harsh engine room environments is used. The cable for each circuit is sized so it can carry the anticipated load and then some without getting too hot. Cables are installed in a manner to prevent chafe and loose connections.

If a fault or short circuit does develop then a fuse or circuit breaker comes into action to shut the circuit down and prevent a meltdown or fire. Incidentally, blown fuses and tripped breakers should be treated as early indicators that there is something wrong that, given the right set of circumstances, could start a fire. This is a time to investigate the problem instead of slapping in a larger fuse or breaker and continuing on. Substituting a larger fuse or circuit breaker in an existing circuit should never be done unless a professional has deemed it safe and reliable.

There are also plenty of non-electrical design and building practices aimed at fire prevention. Fire retardant materials that can withstand extreme heat without igniting or burning are used in prescribed areas, proper distances from hot exhaust components are observed and, with any installation involving gasoline or propane storage, a long list including adequate ventilation and ignition protected components is adhered to.

Electrical System Upkeep

Even though great pains are taken to install a proper electrical system, the system itself should be considered a maintenance item. Electrical connections to bus bars, switches, circuit breakers and other electrical components should be checked for tightness and corrosion on an ongoing basis. Even though connections are made in accordance with ABYC guidelines to minimize tightness and corrosion issues, over time the marine environment, boat vibration and the expansion and contraction of conductors due to temperature changes (thermal cycling) can still cause connections to become loose and/or corroded.

Loose and corroded connections can cause electrical resistance that can lead to heat buildup in conductors, which can cause wire insulation to melt or burn and potentially start a fire.

One area to pay particular close attention to is shore power inlets – Boat U.S. estimates that 4 percent of boat fires are caused by problems in this area. Corroded or loose shower power connections can create increased resistance. Again, with electricity increased resistance always results in heat – sometimes enough to start a fire. Any blackened or burned shore cord ends should be replaced, and the cause should be investigated.

Wires throughout the boat should also be checked for chafing on an ongoing basis. Even though original system wires are protected from chafing in accordance with ABYC guidelines, boat vibration can still cause unanticipated chafing issues to develop.

Be sure all power is turned off to components before touching any wires (this includes disconnecting the DC input to the inverter(s) – the easiest way to do this is to remove the DC fuse near the inverter). Routine spot checks should be carried out monthly to check for loose and corroded connections and that existing chafing protection is in place and is providing proper protection. A complete electrical system check should be carried out annually to fix any poor connections and shore up any insufficient chafing protection. It is best to rely on a competent ABYC-certified marine electrical technician anytime significant updates, changes or modifications are made to the electrical system.

Suppression

In spite of all best efforts and intentions, boat fires do happen. This is where the ability to respond – and respond quickly – can make a difference between life and death. In the case of Nordhavns, fire suppression is provided by automatic extinguishers in engine compartments and most other machinery areas, portable extinguishers throughout the boat, and raw water fire hose stations on some of the larger boats.

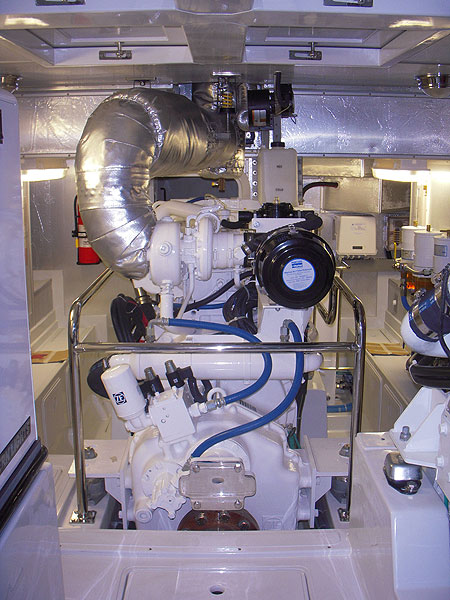

According to the U.S. Coast Guard, 90 percent of all boat fires that occur in open water while underway originate in the engine room or with a boat’s propulsion equipment, so it makes perfect sense to protect these areas with automatic fire suppression systems. And, when you consider that on a Nordhavn an engine room fire could go undetected for some time because the occupants are often two or three levels above the engine room, it makes even more sense to install an automatic fire suppression system.

The automatic systems on Nordhavns are relatively simple in terms of how they work. A pressurized extinguisher bottle containing clean agent FM-200 is placed in the compartment to be protected. The bottle is sized to protect the volume of the space, and the bottle nozzle includes a fusible link that will melt at 175°F. It won’t take an engine room fire long to heat the space up to 175°F, so the extinguisher should actuate early enough to prevent extensive damage. The FM-200 itself is non-toxic and will not leave any residue or damage equipment.

However, the FM-200 will displace oxygen and, depending on the fire, can mix with the byproducts of the fire to create a toxic environment – both of which can be dangerous. All automatic systems also include manual actuation pull cables that can be actuated from outside the space. One important note: The doors/hatches to the machinery spaces protected need to be kept closed for these systems to work effectively – particularly while underway when a machinery space fire is most likely to occur. Otherwise the suppression agent could be allowed to escape to another compartment or outside the boat.

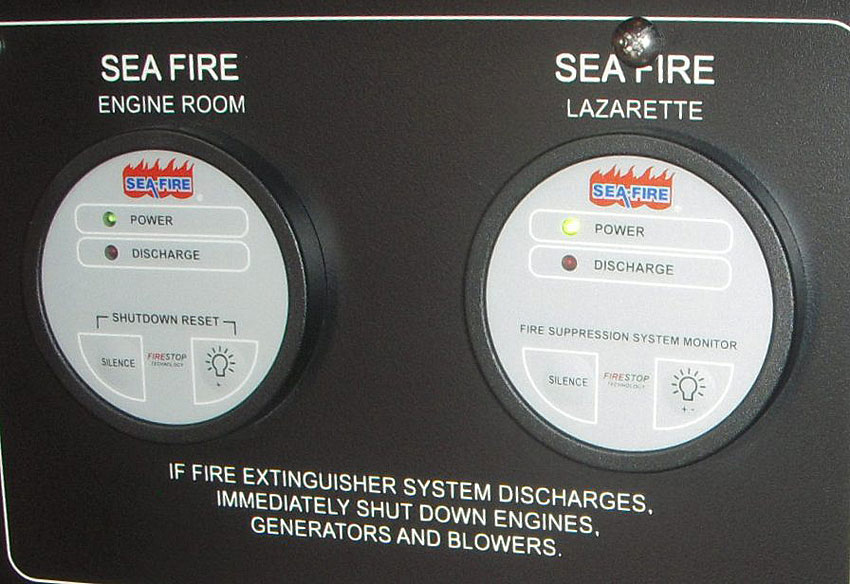

If engines, generators, blowers and some other types of machinery are preset, the automatic system will shut this equipment down when the extinguisher bottle is actuated. This will prevent the equipment from consuming the clean agent and exhausting it from the space, which could prevent it from putting out the fire.

Small control panels for the automatic systems are provided in the pilothouse. During normal conditions they will show that the systems are energized and the bottles are charged. Depending on the system they will also allow the operator to reset the shutdown function after a fire so the engines, generators, blowers and other equipment can be started. Some of the more elaborate systems on the larger boats include separate zones of protection with integrated high temperature alarms and smoke alarms.

Maintenance for the automatic system is relatively minimal. The pilothouse control panel will indicate if the shutdown system is powered, and a dial indicator on the extinguisher bottle itself will show if the bottle is pressurized. Routine system checks are recommended, and an annual inspection by a professional should be done, which includes removal of the extinguisher bottle so it can be weighed. The shutdown system should be tested yearly to ensure all the relays are working properly.

Detection

Even though 90 percent of boat fires are likely to begin in the engine room, what about the other 10 percent? Appliances that cycle on and off, cigarette smoking, and electric space heaters are just a few of the things that can cause a fire outside of the engine room. Besides the obvious danger from a fire, there’s also the danger from smoke inhalation – which is responsible for the majority of fire deaths ashore. Smoke detectors in normally-occupied accommodation areas as well as the engine room can give early warning of a fire – and being able to get just a minute or two ahead of a fire can mean the difference between putting out the fire and having to abandon ship.

While the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) recommends smoke detectors on boats 26-feet or larger with sleeping areas, ABYC does not require smoke detectors at this time (but there are efforts being made to get this requirement into the standard). Nordhavn has decided to make smoke detectors standard equipment on its new boats, and recommends owners of older boats install detectors aboard their boats as well.

It’s best to use UL 217 listed smoke detectors approved for use on recreational vehicles (RVs), which have to stand up to the elements better than detectors approved for residential use. There is a UL standard for marine use, but to date no smoke detector manufacturer has submitted a device for marine approval. There are also detectors that can communicate with each other so if one goes off in one area it will set off all the other detectors aboard to ensure the operator is alerted no matter where he is on the vessel (these detectors may or may not be UL 217 approved). Regardless of what kind of detector used, something is better than nothing.

Portable Extinguishers

Portable fire extinguishers are one of those areas where there are actual laws on the books. The Code of Federal Regulations (46 CFR 25 to be exact) requires a certain number marine-type fire extinguishers to be provided based on the size of the boat (there can be additional requirements for boats going to foreign markets). Extinguishers are classed by what kind of fires they are intended to put out: (A) solids, (B) liquids and (C) electrical fires.

At the minimum a marine-type hand-portable fire extinguisher is a Coast Guard-approved Class B-I or B-II extinguisher. Marine-type extinguishers are available that can cover two or all three types of fires, and ABYC recommends multi-purpose Class ABC extinguishers for use on boats because there’s plenty of wood, mattresses, fiberglass, fuel and electrical components to fuel a fire on a boat.

Accessibility is key when it comes to portable extinguishers. Response time is critical, and the best extinguisher in the world will do no good if it’s buried and forgotten in the back of a closet behind a stack of books and towels. Nordhavn makes an effort to locate extinguishers in readily-accessible low-profile locations when exposed, or immediately inside the door when placed in a cabinet or closet.

Portable fire extinguishers are also a maintenance item. You may walk by that extinguisher in the passageway 50 times a day and feel like you’re prepared for the worst every time you see that little bright red cylinder. But just because it’s there and painted red doesn’t mean it is going to work. All portable extinguishers should be checked monthly for indication of proper pressure as well as for signs of physical damage, corrosion, leakage or clogged nozzles.

It is strongly recommended that a monthly log be kept noting the age and condition of each portable fire extinguisher. Yearly inspections should be made by a professional to determine the health of portable fire extinguishers. The worst time to discover you’re extinguisher is a dud is right after you pull the pin and try to put out a fire.

One interesting development that recently came to light is there have been reports of dry chemical extinguishers not working, even though they checked out fine with proper charge, weight and pressure. The reason is the chemical inside the extinguisher can become compacted over time and basically form a solid cake of chemical in the bottom of the cylinder (and the constant motion and pounding of a boat actually exacerbates this). There’s still plenty of pressure in the cylinder (typically nitrogen is used to provide pressure), but when you pull the pin and squeeze the handle all you get is a blast of pressurized gas instead of the chemical firefighting agent.

Any dry chemical extinguisher that has been sitting on a boat for 3 or 4 years is a prime candidate for this kind of problem. Fire protection specialists recommend doing what they call a yearly “tear down,” which is basically discharging and refilling the extinguisher to ensure it is operational. Also, a good way to mitigate this problem is to remove the extinguisher from its mounting once a month, flip it upside down, give it a few hits on the bottom with a rubber mallet and then shake it vigorously.

While it’s nice to know boat fires are exceedingly rare, and Nordhavns are built using the latest fire detection, prevention and suppression knowledge and equipment, operators should still take fire preparedness seriously. Maintenance of the electrical system, knowledge of how the automatic fire suppression system works, the use of smoke detectors, and the readiness and accessibility of portable extinguishers are all areas operators can focus on to ensure security and safety.