Tech Talk - The Sea Chest Debate

During training as a ship’s engineer the first prank the Chief Engineer pulled was asking me to go fetch the keys to the sea chest. Fortunately I saw through this one (he did catch me off guard with others). And I’ll never forget when one of the other cadets came up to me and asked, in a serious, hushed voice, if I knew where the keys to the sea chest were. Poor, clueless fella.

Those who do know a thing or two about sea chests pretty much agree they are a key element of a large ship’s cooling system. However, there is a healthy debate about whether sea chests merit use on recreational trawlers like Nordhavns. Every now and then we get pulled into the discussion when someone asks if we can use a sea chest on a new boat instead of individual thru-hulls. The answer is always the same: “Of course we CAN, but we’re not sure we SHOULD.”

Chests Full of Treasure

The argument for a sea chest is certainly compelling. For starters it gathers most or all of the raw water inlets into a central, easy-to-access location. No more having to wedge into impossibly tight areas in multiple compartments to reach an inlet thru-hull, and no more having to remember where a certain inlet valve is located. There’s no denying that this kind of operational convenience is to die for.

Depending on how the sea chest is designed it can have a single strainer basket for the entire chest, thus eliminating the need for smaller, individual strainers for individual thru-hull inlets. No more cleaning multiple strainers buried below deck hatches scattered all over the boat.

Then there’s the danger of flooding from a damaged or faulty sea water inlet line somewhere on the boat. It might not be immediately apparent exactly where the water is coming from. If the sea chest has an isolation valve or other device to cut off the flow of sea water you can quickly stop the flooding even if you have no idea where the water is coming from.

It’s not hard to see why anyone who has ever struggled to open (or even find) a hard-to-reach inlet valve could easily be sold on the idea of a sea chest. Then add in the opportunity to omit all the little individual strainers and the benefit of being able shut down any flooding quickly and easily. Pretty soon you begin to wonder why a sea chest isn’t standard equipment on all boats.

All That Glitters is Not Gold

Obviously sea chests are far from universal equipment on boats. The list of detractors is actually quite long – and it doesn’t take much to tip the scale in favor of individual thru-hulls. Like with many things on a boat, the bigger the boat gets the more flexibility there is to do things that just don’t make sense on smaller boats. Sea chests are no exception.

First off there has to be a good place to put the darn thing – and that can be a real challenge on a small boat. If the sea chest has to be crammed under the engine room deckplates (and completely below the waterline) with marginal access to all the valves then you’ve already lost much of the utility a proper sea chest is supposed to provide. You won’t be able to put a strainer basket inside it because the top needs to be above the waterline to be able to open it for cleaning. So instead of an actual cavity in the hull open to the ocean you’re left with box fed by seawater via a large thru-hull, hose and strainer.

Now the sea chest basically becomes an interior manifold with one or two relatively narrow thru-hull openings to the sea. This is a far cry from a nice, large, open hull cavity with gobs of flow and plenty of interior side room for convenient access and head room to lift out a strainer basket.

Whether it’s a big or small boat, there is the inherent danger of the hull opening becoming plugged or blocked and starving everything of sea water. The standard way to mitigate this is to have openings on both sides of the hull. For larger boats this means having two sea chest risers with strainer baskets in each and a common header in between – but this takes a lot of room. On a smaller boat with the manifold style sea chest this means thru-hulls and strainers on each side leading to the chest. In both cases one side needs to be able to meet the sea water demands for the whole vessel.

Fouling can also be an issue. There’s opportunity for marine growth as long as water is flowing through the chest. Even if only one or two items are running – like a generator and the air conditioning – all the inlets in the chest are going to be impacted by fouling. And if the chest is completely below the waterline, you’ll have to shut everything down so you secure both inputs and remove the cover for cleaning. Also, a central sea chest often means longer plumbing runs from the chest to the equipment than there would be with individual thru-hulls – and longer runs can be more susceptible to fouling than shorter runs.

The likelihood of including ALL the sea water inlets in a sea chest can be slim, especially if it’s a wet exhaust boat. The sea water demand for a wet exhaust engine is going to be much more than that for the generators, air conditioning pump, water makers, etc. The sea chest would have to be big enough to satisfy the needs of the engine without starving any of the other consumers – which brings us back to finding room for a big-enough sea chest in a limited engine space.

A common compromise here is to give the engine a pair of dedicated thru-hulls and strainers (one set for backup), and find room for a smaller sea chest for the other consumers. Even then there can be some items that are just too far away, like a chain-wash pump, water maker or other device located all the way forward.

Then there’s the often-heard comment about a sea chest reducing the number of holes in the boat from many to one. That’s technically false, because there are still the same number of holes below the waterline – with each being a potential source of flooding (although a sea chest can offer the advantage of shutting them all down at once). Also, there’s no change in the number or location of the discharge thru-hulls, so you’re still faced with multiple thru-hulls scattered about the boat.

We’ve Built a Few

Nordhavn has used sea chests on a number of smaller boats in the past, and we continue to use them on our largest boats.

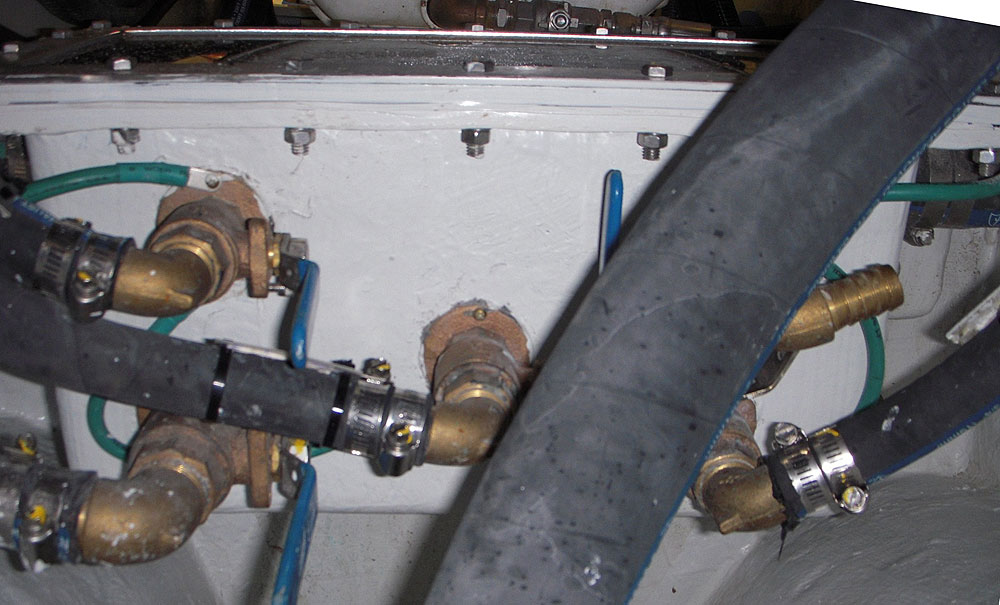

The smallest boat in our line to use a sea chest is the N55 (and N60). From day one this boat was designed to use the manifold style sea chest described earlier. The inlet thru-hulls and strainers are low to the hull on each side of main engine, with each feeding the sides of the sea chest located just aft of the engine below the prop shaft.

This arrangement definitely has its limitations in terms of accessibility and convenience. It’s completely below the waterline, so it has to be entirely secured to remove the bolts and cover for cleaning and maintenance. The valves for the consumers are directly below a spinning shaft – not exactly ideal. And in some cases it made sense to provide individual thru-hull for specific items, especially those all the way forward.

While this setup has been successful on countless N55s and N60s, recent engine changes have tilted the balance in favor of individual thru-hulls. The new standard engine would force the chest to be located even lower than it already is, and the sea water demand for the new wing engine is too much for the sea chest to handle in tandem with all the other consumers. As a result we no longer use a sea chest on these boats.

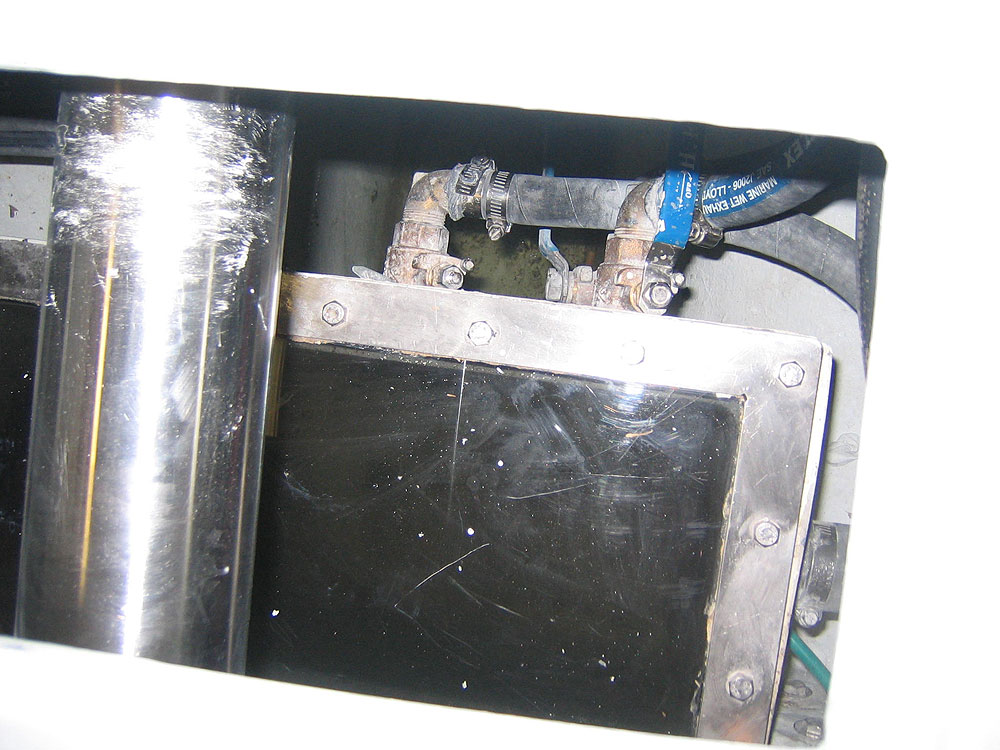

On a larger boat, a new N68 build a few years ago, we had an interesting project where the owner requested a full-fledged sea chest with an internal strainer basket and everything. Thankfully there’s enough headroom in the N68 engine room to get the top of the sea chest above the waterline and still have enough clearance to lift the strainer basket out for cleaning. The only consumer that is not supplied by the sea chest is the anchor wash pump all the way forward in the bow machinery compartment. Everything else, including the wet-exhaust main engine, is supplied by the sea chest.

It would seem that the sea water supply would be cut off to everything if this sea chest somehow became blocked, but that’s not the case. There is a thru-hull on the opposite side of the boat that can supply the sea chest and/or main engine in the event the main sea chest opening becomes blocked. All things considered, this was a really well executed sea chest arrangement – and we’re told the owner has had great success with it.

Both of our really big boats, the N86 and the N120, employ the sea chest concept, but in different ways. The N86 is similar to the N55 with a large enclosure centered in the engine room and completely below the waterline. Like the N55 there are dual thru-hull inlets with strainers that feed the sea chest. The N86 is a wet-exhaust, twin-engine boat, and it made more sense to give each engine a pair of dedicated thru-hull inlets (one on each side of the hull for each engine) instead of building in a pair of huge sea chests that could handle the engines and all the other consumers.

The N86 is a big boat, but it would still be a challenge to fit in a pair of well-placed sea chests with strainer baskets. So the engines get their own thru-hulls, leaving the smallish sea chest to supply all the other consumers except for the chain wash, aft fire pump and air conditioning pump (this is so the air conditioning pump running 24/7 in port won’t foul the whole sea chest).

While the N86 setup is similar to the N55, there is one big difference: There’s plenty of room to get at the sea chest and all the valves on the N86. The chest is located below the deck between the engines, as are the inlet valves and strainers for the sea chest. You can actually stand on the inside surface of the hull and easily get at all the valves, strainers and the top cover bolts.

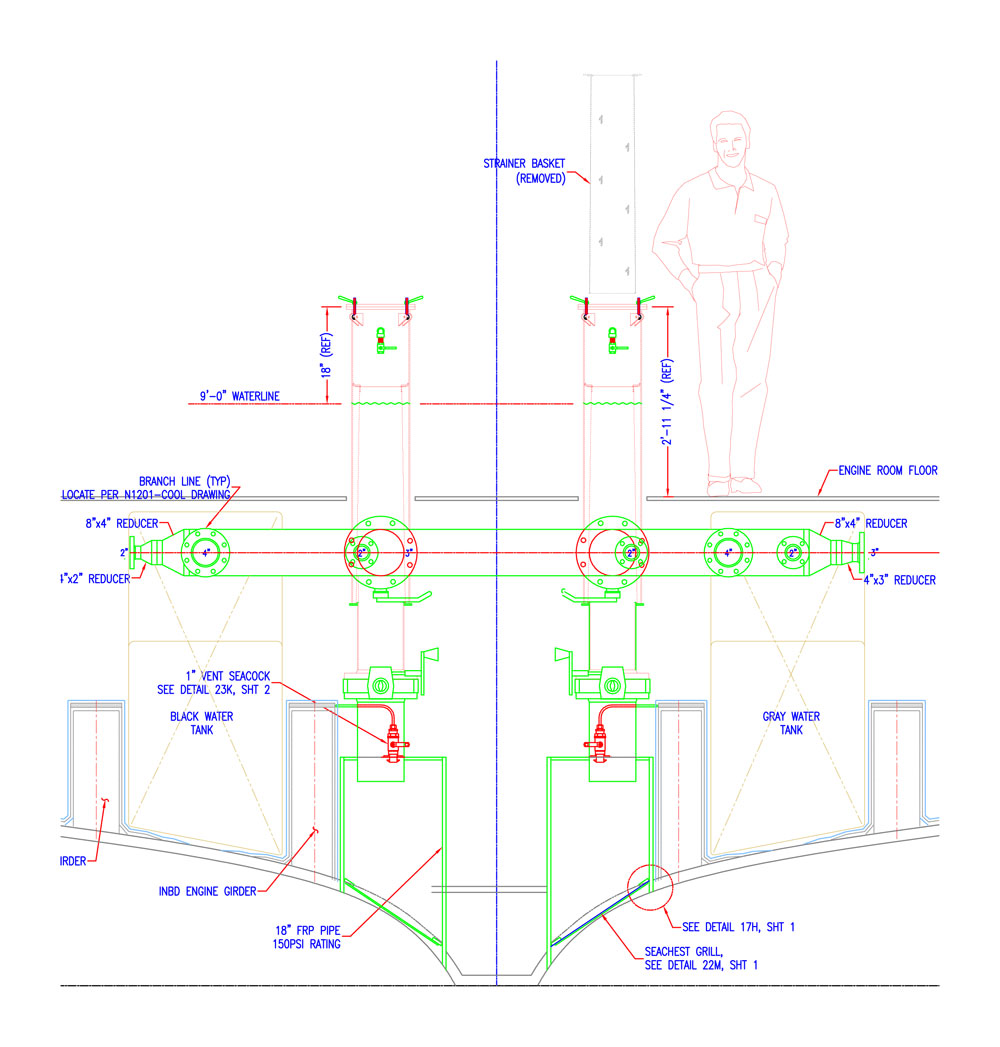

On the N120 with its two-story engine room we finally have the space to go big and put in dual riser sea chests with strainer baskets in each and each connected to a common distribution header. This is pretty much the ultimate setup. Either sea chest can be isolated for strainer cleaning and maintenance underway without having to take any equipment out of service. There’s even little blow-down valves for eachthat inject compressed air into the sea chest to clear away any bags that might get caught in the intake grate. Virtually everything that needs sea water on the boat is supplied by these two sea chests. The only exception is a dedicated fire pump intake that is located all the way forward.

The Debate Goes On

To me the idea of a sea chest is a no-brainer – no one can argue against the improved convenience it can bring an operator. But the reality is much more muddied. There certainly comes a point when forcing a sea chest in to an entirely unfriendly space is hardly worth doing. There’s also an element of personal preference. While some value the pros like the convenience and simplified cleaning, others find the cons like the potential for fouling or losing all service due to a blockage reason enough to stick with individual thru-hulls.

Then there’s our point of view as a builder. We’re obviously not completely for or completely against sea chests. They certainly become more attractive as the boats get bigger and the ability to install, operate and service them improves. On the smaller boats it’s really tough to make a good case unless you’re willing to settle for something much less than a proper sea chest. On the medium boats is probably where the most gray area exists. It’s been demonstrated that it can work on an N68, but it might not be everybody’s cup of sunshine. Besides, taking that one example and making it standard on all future boats that size is much easier said than done.

It’s a lively topic, but I don’t expect that the matter will be settled any time soon. Now, who has the keys to the sea chest?