Sleipner Vector Fin Stabilizers

Stabilizing systems have long been used on large yachts and they are working their way down into smaller boats. For a long time, straight-fin systems had been the go-to for stabilization but Sleipner, which is known for its bow and stern thrusters, has developed Vector curved fins. The manufacturer says the curved design is up to 50% more efficient than straight fins and results in virtually no loss of speed.

Captain’s Report

Overview

Stabilizing our boats has long been a consideration. It requires modifications to the boat in one way or another, since manipulating the water hasn’t proven successful — at least on this side of the Old Testament. For owners looking to install stabilization on their boat, the choices are vast: Straight fins, curved Vector fins, paravanes and even gyro stabilizers.

While all may work, the styles and choices produce very different results. A version that warrants some consideration is the Vector — or curved fin version from Sleipner — the company well known for its bow and stern thrusters. And here’s why.

How do fins work?

Remember when you were a kid and stuck your hand out the car window and moved it up and down in the breeze? Well, a fin works the same way, similar to the way an airplane’s ailerons (flaps at the trailing edge of the wing) keep the plane level or allow it to bank into a turn. Fins work to counter the movement by moving opposite the force. The flow of water over the fins creates pressure on one side of the fin and suction (lift) on the other.

The combination of these forces counteracts the boat’s desire to roll with the wave. In fact, that force increases exponentially with boat speed so the faster you go, the better the fins work. For a little roll to port, the fins angle to starboard, which returns the boat to neutral or even stops it from moving from neutral. The larger the wave, the greater the movement of the fins. The faster you go, the less movement is needed.

Will fins even work on my boat?

This is, of course, the first consideration. While the concept seems simple enough, the simple fact is that fins aren’t the answer for every boat. Fins work best on a boat with longer roll periods and the larger the boat, the longer it takes to roll. This makes sense if we take the idea to the extreme and picture your heavy mother-in-law stepping onto your 20’ (6.1 m) bowrider. The side dips quickly and then recovers just as quickly. This is why fins aren’t typically found on boats smaller than 48’ (14.6 m).

Why Vector fins over straight?

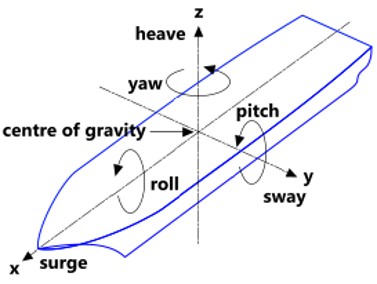

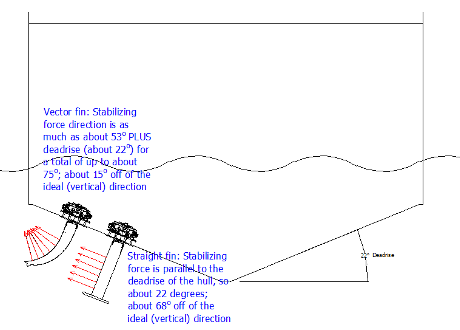

Ideally, the fins would stick straight out from the side of the boat, parallel to the water surface. These would be essentially the same as ailerons on an airplane wing and just as effective. However, such a system is impractical on most yachts due to cost. The next best thing is to mount them on the bottom of the boat sticking downwards. If they pointed down vertically, they would essentially be rudders and therefore virtually useless as stabilizers. Luckily, most hulls aren’t flat where the fins are located — they're angled. This is called "deadrise." A typical deadrise angle on modern yachts is about 20-24 degrees or so where the fins are usually located. But that’s a far cry from 90° and so the straight fins are limited in their ability to prevent the boat from rolling. The downward angle causes some undesirable effects, such as sway and yaw, in addition to the desired stabilizing effect.

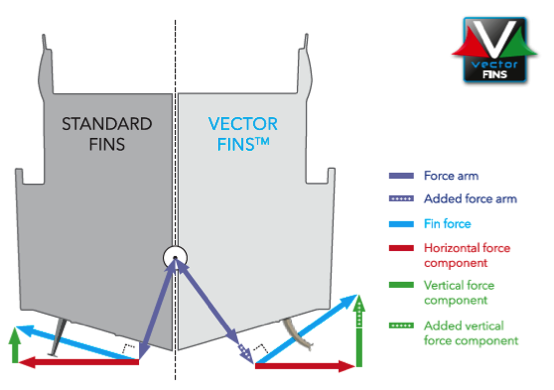

Vector fins are curved about 36 to 53 degrees upward (depending on the fin size). So, the curve angle plus the deadrise angle combine to direct the stabilizing force significantly more vertically and that makes them far more effective in preventing boat roll. The fin’s anti-roll force is directed vertically, the more effective the fins will be and unwanted side-effects such as sway and yaw are reduced proportionally.

The Vertical Force Component

Straight fins are mounted to the boat parallel to the angle of the boat’s bottom — the deadrise. They have a minimal vertical force component and more of a horizontal component. Now mount the curved, Vector fin in the same position. The curve naturally provides more resistance in the vertical component and less in the horizontal. Presto, more resistance to the roll. Typically 30 to 50-percent more in fact.

Better Efficiency Underway

Roll resistance is all well and good, but there’s another inherent problem — resistance to forward motion through the water, aka "drag." Straight fins create drag and slow the boat compared to having no fins. Vector fins also create drag. However, due to their form shape, they also create a great deal of lift — enough to offset up to 100% of the drag. This results in virtually no speed reduction compared to having no fins.

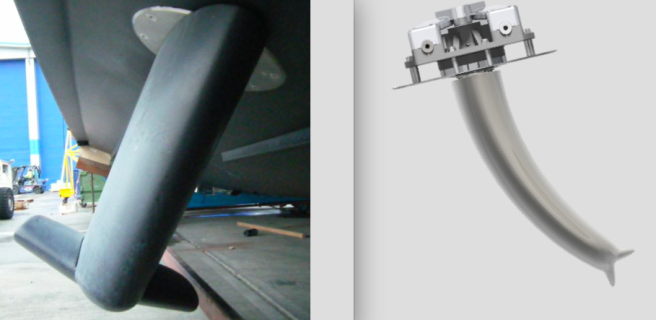

Sleipner's Vector fin has its curve from top to bottom when viewed from the side. They’re thinner in the cross-section and carry small winglets at the tips that, much like an airplane’s wing, reduce turbulence and drag. These factors all add up to no loss in speed when Vector fins are installed. Better performance translates directly into better fuel efficiency.

What about at rest stabilization?

When at anchor or on a mooring, gyro stabilizers have an advantage over any fin. If the boat was only going to be moored then the decision would be easy, but the darn boats were meant to travel. So, there’s a tradeoff of sorts when it comes to at rest stabilization. Whereas fins get their power from waterflow over the fin when underway, just like airflow over an airplane wing, there is no flow at anchor. So, what to do? When the boat isn’t moving forward, the fins change their mode of operation, going into full sweep mode. They sort of use the water as a solid and the movement of the fins push against the water to “lever” the boat against the roll.

Remember that thing about boat speed increasing the stabilizer force? Since there is no speed when at anchor, the fins need to be bigger than for just underway stabilization. The thing about Vector fins is that increasing their size won’t result in reduced underway speed or increased fuel consumption, unlike with flat fins. When comparing straight fins to Vector, again the Vector comes out the clear winner.

Are the hydraulic actuators any different with Vector fins?

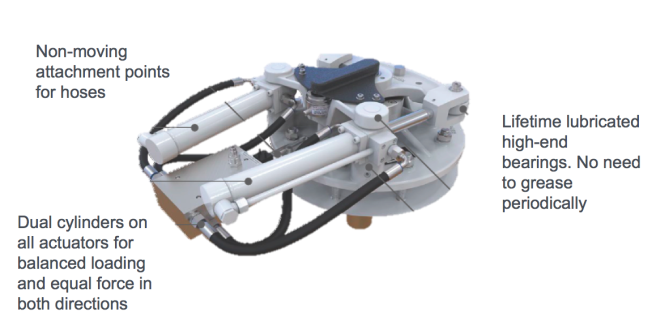

Firstly, the actuators used by Sleipner are dual cylinder, so they produce the same force in both directions. The single-cylinder installations used with many straight fins are about 30-percent less powerful in one direction than the other. Having two cylinders means the actuators are every bit as powerful rotating the fin to port as it is to starboard. Makes sense!

The smaller Vector fin sizes use a “rack and pinion” style actuator, which has almost no moving parts, and that’s always a good thing. They have no bearings on the cylinders and rod ends to worry about. And all actuators used on the Vector fins are virtually silent.

Just keep swimming…. Just keep swimming….

There’s another side effect with straight fins when moored, actually with any fins when moored: Swimming.

“Sculling” is propelling a boat through the water by quickly swinging the rudder back and forth. It’s not entirely efficient but it works. Well, the same thing happens with heavy rolling when fins are used. They scull the boat forward on its mooring if there’s no wind or current to offset it. Not enough to take off mind you, but it’s there, nonetheless. Enough to cause concern in a crowded anchorage to be sure.

Vector fins scull less because of their geometry since, as we discussed, more of the force is applied to the vertical than the horizontal. From the control panel, Sleipner also has the ability to disable one fin and/or reduce the “gain” while at anchor further reducing the minimal swim effect by half.

What about gyros?

There’s no doubt that gyro stabilizers have had a tremendous success story, but they aren’t without their drawbacks either. Gyros are great “at anchor” or at low speeds before a boat gets up on a plane, but they rapidly lose their effectiveness at speed. Fins, on the other hand, get more and more effective the faster you go, and that’s a good thing since a boat gets stiffer and thus harder to stabilize the faster you go.

The Bottom Line

No system is perfect and no boat is perfect. Just as with a boat purchase, the choice of stabilization systems takes careful consideration of how the boat will be used, where, and in what conditions. Gyros have their place in small boats, trawlers and sportfish boats (boats that really back down hard), and certainly in the dockside party. Paravanes have their place in commercial boats that care little about looks and less for complicated systems that aren’t bulletproof. Fins are the choice for the distance cruiser, and clearly, there’s a distinction between straight and Vector fins. Regardless of the choice, it’s clear that there’s no shortage of innovation still going on in the science of stabilization.