Drugs, Sex & Pirate Radio

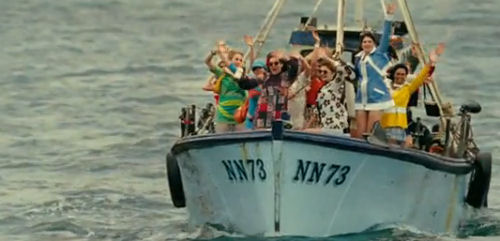

Last Friday a new movie opened around the U.S. titled “Pirate Radio” which dramatizes a period in British history during the 1960s when the U.K. government owned and monopolized the air waves -- and banned rock and roll! (Do you think Vlad Putin was taking notes?) Hard to believe, but true. Ironically, it wasn’t Tories or Labor or some off-the-wall libertarians who threw themselves on the barbed wire of government control, but rather it has a bunch of hopped-up DJs. It all takes place on boats anchored off the east coast of England in the North Sea which is why were are telling the tale...and we enjoyed the movie.

The Boat That Rocked: Radio Caroline, broadcast at sea from the vessel Mi Amigo, was one of the many pirate-radio stations that anchored off the coast of England during the 1960s. The stations flouted British law with their illicit rock 'n' roll programming. |

See the official trailer for Pirate Radio--

The Real Story Behind Britain's Rock 'N' Roll Pirates

by Vicki Barker

Reprinted from the NPR website

At the dawn of the 1960s, Britain still bobbed to the rhythms of a vanished age. With the exception of one commercial TV network, the airwaves were owned by the British Broadcasting Corp. — known semi-affectionately as "Auntie."

The BBC favored a bland if nourishing diet of news, information, light entertainments and children's programs. In other words, the rock 'n' roll revolution that was spreading like wildfire in the United States had been all but banished from the British airwaves.

The ship used in the movie “Pirate Radio” is a close replica to some of the actual ships used to break down government control of British air waves. |

But for a group of rebellious, rock-loving disc jockeys, such restrictions were merely a hurdle. Many of them took to the seas, hunkering down on old fishing ships anchored off the Eastern coast of England; from there, they broadcast programs built around the illicit tunes of bands like The Hollies and The Rolling Stones.

In 1967, the British current-affairs show World in Action shot a program about pirate radio aboard the Mi Amigo. Here, World in Action team members Mike Hodges and Paddy Searle shoot footage of DJ Robbie Dale in the ship's studio.

In 1967, the British current-affairs show World in Action shot a program about pirate radio aboard the Mi Amigo. Here, World in Action team members Mike Hodges and Paddy Searle shoot footage of DJ Robbie Dale in the ship's studio. |

Richard Curtis, director of the new film Pirate Radio, which is based on these events, was an 8-year-old boy confined to a posh boarding school when he first heard the broadcasts. While he wasn't allowed to listen to music during the day, he remembers hiding a radio under his covers at night .

"And what I heard were these extraordinary pirate-radio stations," says Curtis. "These fantastic guys floating out in the middle of the ocean, pumping rock 'n' roll into my private school all night."

British Pirates in International Waters

pirates' off-coast locations strategically put them in international waters — and thus out of British authorities' legal reach. When they began broadcasting in the mid-'60s, their signals reached as many as 20 million Brits — nearly half of a population that had been permitted a diet of only six hours of "pop music" a week. And the pirates' playlists were largely lifted from American Top 40 stations, which during the '60s were dominated by the era's British bands. Radio Caroline, which broadcast from the ship Mi Amigo, became one of the most popular stations.

was bizarre" says Dave Cash, a former Radio Caroline DJ, "because you had no real idea of what you were doing until you came ashore. And there'd be 3,000 people waiting for us." The DJs were treated like pop stars themselves — and since most were young and single, they took every advantage of their newfound fame.

David Cash was the co-host of the Kenny and Cash Show on Radio Caroline.

David Cash was the co-host of the Kenny and Cash Show on Radio Caroline. |

At sea it was another matter. The acoustics on the steel ships were subpar, the onboard regimen was monastic — no women allowed — and the weather could wreak havoc. During winter storms, the DJs might be stranded onboard for a month or more.

Keith Skues, who hosted one Radio Caroline show, said one of the main challenges was the turbulence. "The fact that you're being kicked out of your chair across the studio didn't seem to matter, as long as the records didn't jump," says Skues. "And of course they did."

Some of the biggest bands of the period, including the Stones and The Dave Clark Five, got their first exposure on pirate stations. The pirates also played commercials, which was unheard of in the United Kingdom at the time.

Government Crackdown

After British law disbanded most of the pirate stations, many of the DJs went to work for the BBC. Dave Cash (fourth from the left) and this group of ex-pirate DJs helped the corporation launch its first pop music station.

After British law disbanded most of the pirate stations, many of the DJs went to work for the BBC. Dave Cash (fourth from the left) and this group of ex-pirate DJs helped the corporation launch its first pop music station. |

In fact, the prime motivating force behind the pirates wasn't some kind of rock 'n' roll evangelism; it was good old-fashioned profit: American and Irish entrepreneurs ran the two biggest stations, trying to sidestep Britain's refusal to grant radio licenses to commercial broadcasters.

In 1967 the British government made it a crime to supply music, commentary, fuel, food and water — and, most significantly, advertising — to any unlicensed offshore broadcaster. The law sounded the official death knell for most of the pirate stations. Yet the music had made its mark. One month after the law took effect, the BBC launched its first pop station. And in a strange turn of events, many of the shipwrecked DJs went to work for their former nemeses at the BBC. After all, it would be six more years before Britain allowed any commercial radio stations in the country.

"They hated us," says Cash, who still works for the Beeb, "but we didn't care. And we still don't! I take their money, but I still don't care. And if you need a real pirate over there in America, I'm your man."

According to the movie script women were banned from the Pirate Radio ships except one weekend every two weeks when they were allowed to visit for a little R&R for the love-starved DJs. |