Expect the Unexpected

By Dag Pike

Trying to be safe at sea is mainly a question of trying to think about things that could go wrong and anticipating them so that there is already a solution in place. Hopefully, the boat builder and designer have done their jobs and produced a reliable boat. In many cases, you will have two engines so that if one fails you can at least get home on the other one.

Where are You?

Start by having two GPS receivers and one of those is portable and battery-powered. So, even in the event of a full electric failure, you can still navigate home -- although with modern engines an electrical failure will also put the engines out of action in most cases.

Quo Vadis?

These days, there seem to be two types of uses that owners of large boats put their vessels to. 1) Entertaining at the dock, and going from quay to a beach to anchor for a couple of hours, then back to the dock. 2) Boaters who like to do serious cruising, going out to the islands, taking long coastal passages offshore, or across large bodies of water such as the Gulf of Mexico. This report is intended for Group #2.

When you go to sea, you want that reassurance of reliability. You should aim to be self-sufficient and be able to cope, at least temporarily, with any emergency. Unfortunately, not all offshore boats are the same. While some are better than they used to be, staff turnover, turning the screws on the budget, lack of design foresight and offshore experience still separate the well-found boat from the ones used for traveling from dock to beach and back. Those boats should be purchased by Group #1, and they are.

Weather Factors

Even with a reliable boat, one of the big unknowns is still the weather. Weather forecasts these days are like magic, and they probably get it right about 95% of the time. Even when the forecast does not quite match the conditions you are experiencing, and the conditions are worse than expected, you should have a boat that can cope with more extreme conditions.

You should very rarely be driving your boat close to the edge of its capabilities because, after all, you go to sea for pleasure. So, you should rarely see these extremes.

Coping with Problems

Problems can start, however, when two or more things go wrong at the same time. That can start to challenge your resources. While it may be very rare, you will still have to cope.

Domino Theory. What you don’t want is a compounding situation, where one thing has gone wrong and starts a chain reaction, leading to something else going wrong and so on. It can be a slippery downhill slope. Still, you need to be able to cope because you are on your own, at least initially. This is where the handbook runs out of steam and you have to invent solutions.

Mystery Situations. What's much harder to cope with are those mystery situations where you can’t work out what has gone wrong. So, it can be much harder to find solutions. These are what I call unexpected situations where you are in a dilemma about the cause of the problem. Until you have found that cause, it can be hard to find a solution.

At sea, you can’t walk away from a problem and get someone else to deal with it. You have to find that solution. However, you occasionally come across an event at sea that does not make any logical sense.

Bad Timing

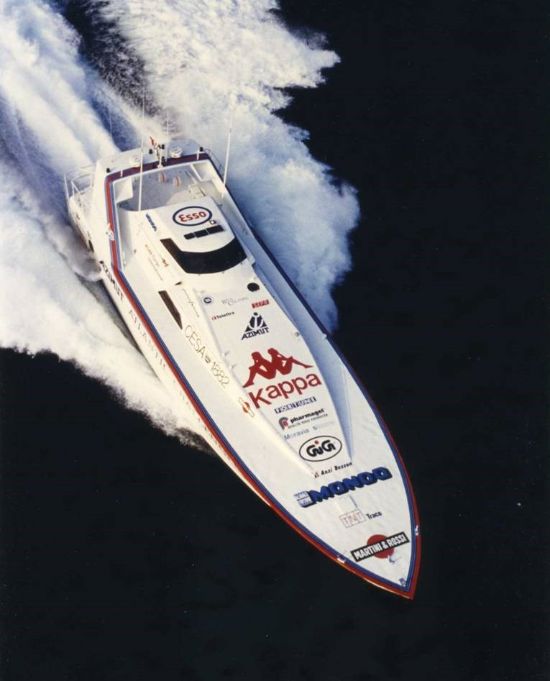

I have come across two of these inexplicables, and they never seem to happen at a convenient time. The first was when we were 500 miles from the nearest land, not the best place for an emergency. The boat was an Azimut Atlantic Challenger, an Italian boat designed to cross the Atlantic at record speed without refueling.

She was quite a remarkable design, an 80-footer weighing 40 tons when empty. She was able to carry twice her weight in fuel. We were en-route from Gibraltar to the Azores as part of the delivery trip to get the boat to New York, ready for our record attempt from west to east.

We were cruising along at a steady 35 knots when the engine compartment started to fill with water. Not a good omen. When we stopped to see why and where the water was coming in, the water stopped coming in and we could pump it out. Once the bilges were empty, we carried on. But again, the engine compartment bilges started to fill. So we pumped out again. When we stopped, no water was coming in.

We searched high and low for the leak, but it was hard to get access to every corner of the complicated engine room with its four large diesels. Underway, even at slow speed, the water was coming in at such a rate that the powerful bilge pump could not cope with the amount of water coming in. So now we were in something of a dilemma. If we moved, we were sinking. If we stopped, we were okay. However, you can't stay stopped forever when you're 500 miles from land.

Finding a Solution. Finally, we hit on the idea of disconnecting the electric fire pump and converting that into a second bilge pump. That was just enough to cope with the inflow if we kept the speed down. Then it was a long and slow journey to Lisbon, the nearest land where dry-docking the boat revealed the problem.

A weld in the bottom of the water jet intake had cracked. When the boat was moving forward, this opened up under pressure and let the water in. When we stopped, the crack closed off and the water flow was virtually stopped. It’s simple when you know what the problem is, but the textbooks don't seem to cover that sort of problem.

Anchor Problems

It was a similar type of problem that caused us a lot of head-scratching one wild and stormy night off the west coast of Scotland. The anchor was dragging, but we could not lift it.

The forecast was bad on our two-handed cruise in a sturdy motor sailer. So, we holed up in what we thought was a nice and sheltered anchorage tucked in close under the lee of the land. The water was shallow enough for anchoring and high mountains should have offered good shelter.

White Squalls. It looked like the ideal spot to ride out the storm, but what we had not bargained for were the wild white squalls that came rushing down the mountainside in our “sheltered” anchorage. They started to hit us like a sledgehammer. It soon became evident that we had to find a better anchorage.

It was quite a relief to escape from those squalls. We found what looked like a better spot a few miles away under the lee of a low-lying spit of land.

Everything seemed to be under control. With the wind whistling overhead, we cooked supper and settled down for the night. It was only when I went up for a last look around before going to bed that I discovered that the shore lights were moving past. The anchor was dragging, which I thought was tiresome at that time of night. I went forward to let out a bit more chain, but that did not work. So, it was time to start the engine and get the anchor up, and hopefully to find a better spot. That was when I discovered the problem. The anchor could not be lifted, yet we were dragging.

I thought I had been clever when we anchored and had attached an anchor buoy to the anchor. Simple, all I had to do was pick up that anchor buoy and lift the anchor with the anchor buoy line. There was no more success heaving on that line. Nothing would move, but we were still dragging.

By this time, I was weighing up in my mind about whether to slip the anchor chain and just get out. But I thought I would have one more go lifting the anchor before taking the drastic step of letting it go altogether.

Not budging. It was now three in the morning. The rain was coming down in sheets and the wind was howling. Using the hand windlass, and with super-human strength, even if I do say so myself, I wound in the anchor chain as far as possible. The bow of the boat was now nearly down to sea level, with the stern sticking up in the air with the weight on the anchor chain.

Still, the anchor would not lift but then I spotted movement in the water. In the dark, I could just make up this huge bunch of kelp and rocks just breaking the surface. There was our anchor chain wrapped around it.

This bunch of buggers was too heavy to lift, but it was nice and slippery. So it was sliding smoothly across the seabed as the wind drove us astern. Once I knew what it was, I lowered it down again until the yacht was riding more or less level, put the engine in gear and thought we would take our chances in deeper water in the hope that the anchor chain would unwind.

Finally Free. With the movement of the boat in the waves combined with the deeper water it finally allowed that anchor chain to shake itself free so that I could wind in the anchor and head towards shelter and respite in the harbor at Kyle of Lochalsh, exhausted but safe. A notice board on the quay said “Keep Clear. Emergency Vessels Only.” I decided we were an emergency and tied up for what remained of a very long night.

I don’t want to put you off boating. It can bring so much pleasure but because you are out there on your own you do need to be resourceful. Of course, you can get help if it is a dire emergency, but I must say that I do find myself reluctant to do this and it has to be a DIRE emergency.

Just be aware that the unexpected can be lying in wait for you out there and at sea do not take anything for granted. I still love going out in the ocean and the freedom it offers.