Auto-Routing Examined: 2 Systems Tested

By Dag Pike

Car navigation has never been so easy since the invention of GPS systems. It’s so simple, just feed in the zip code and the system knows where you are, where you want to go, and it comes up with a suitable route. Why not do the same with our chartplotters? To start with, there is a considerable difference between navigating on land and navigating at sea.

Waterways and Not Like Highways

Out at sea, things are not quite so simple. For a start, there are no pre-defined tracks, except in channels and harbor entrances. So, you are mainly free to roam at will to get to your destination. The depth of water could be a restrictive factor in finding a suitable route. There can be other no-go areas out on the water or under the water that may limit the chosen route, so it is not quite so easy for the computer to work its magic.

Garmin, who were pioneers of road navigation, introduced their auto-routing system for their chartplotters many years ago. Like the land system, you simply entered start and finish points on the chartplotter, and the system would find the route. Now, electronic chart provider Navionics has developed its auto-routing system that does pretty much the same thing. You can find auto-routing on most chart plotters these days.

New Auto-Route Products

The Garmin system was limited to use on their brand plotters. But Navionics does not make plotters, just electronic charts. So, their system has been adopted by many of the electronic majors such as Raymarine and the Navico Group, which includes Lowrance, Simrad, and B & G. Now Garmin owns Navionics, so this is the major auto-routing system available.

Limited Abilities. With auto-routing now available on most chartplotters, it is time to look at what these automatic systems can and cannot do, as well as the risks of letting the electronics take over your passage planning.

Having your route planned automatically would be fine if the seas were not littered with obstructions to navigation both under and above the water. These days, you have to cope with traffic separation schemes, oil rigs, and platforms. Now the first wind farms are appearing in US waters. Also, there are the normal problems of avoiding rocks, sandbanks and shallow waters – to say nothing of other boats.

Navigation has become complicated and the question asked was, “Could auto-routing cope with all of these challenges while providing a safe course that would keep you clear of dangers?” On land, you have clearly defined roads to follow. At sea, there is generally much more freedom to choose your course, but equally a lot of potential obstacles.

Information is Key

Both of the systems tested allow you to put in the draft of your yacht and some other parameters, such as mast height (for bridges), beam, which is assumed to be for canals and locks, and how close you want to pass dangers. As far as the draft is concerned, you don't want to put in your exact draft because the system takes this literally and if you say 6 feet then any water deeper than this is open for navigation as far as the router is concerned.

Mast height and beam only apply to inland waters and canals but the distance off dangers seems to be a bit arbitrary. It is defined by words like “close” and “distant.” If you are going to define this parameter, then it would be helpful to have it as a distance such as ¼ mile.

As with normal navigation, it is up to you to define the safety margins you want to work with, and you have to remember that neither of the two systems takes into account the rise and fall of tides when considering safe water depths. I found this a problem when navigating from some marinas in tidal waters where the auto-routing did not recognize my starting point as the water was too shallow.

Must Be Marked. Unless dangers to navigation are marked on the electronic chart then auto-routing will ignore them. There could be areas of strong tidal currents that you might want to bypass but you are not likely to see these on the electronic charts. The increasing navigation restrictions posed by offshore oil installations and wind farms will only be taken into account if they are shown on the chart, so you need the latest up-to-date charts that show those under construction as well as those that have been completed.

It would be rare to see those under construction being shown. Offshore oil installations and wind farms are the curse of the ocean for boaters in many areas and in European waters you are starting to find them springing up everywhere, increasing the numbers of no-go areas. It is much the same in the Gulf of Mexico.

So, let's look at how the two systems cope with plotting specific routes. This review is not a direct comparison between the systems but a look at how the systems cope with a variety of challenging routes.

We were limited by the charts available for the two systems, which were for the northeast coast of the US and the Seattle area for Navionics, and for the Florida and Bahamas regions for Garmin. In selecting the plotted routes, we have tried to provide a variety of challenges to auto-routing, including sailing from major ports, crossing traffic separation zones, sailing along shipping channels, dealing with wind farms and making landfalls.

Garmin

To start with, a route was plotted from Miami Beach Marina to a marina on Marathon down on the Keys. There are three options when taking this route: the inside channels with lots of shoals and bridges, the inner outside channels that follow close along the Keys but outside them, and then the full outside passage that takes you clear of the inshore dangers and shoals.

The Garmin system chose the last of these three, probably ignoring the inside channel because of the many shallow-water patches (we had entered 10 feet as a safe draft) and this might have been the reason that the inside/outside channel was also rejected.

If I had been navigating, I think I would have chosen this second option because to a degree you are sheltered from the strong current that pours up the Straits of Florida when you go outside. But, given the draft we programmed in, the Garmin system picked the safest route. So, here we see there is still no substitute for a knowledgeable skipper.

The proposed course headed down the middle of the channel, coming out of Miami Harbor after making a dog’s leg from the marina to get into this main channel. Then it made a sharp right turn to pass inside the spoil areas.

After that, it plotted a route that I would have considered dangerous, passing inside the buoys that mark the various shoal patches that exist along this shore, in other words passing between the buoys and the shoal it was marking. I would never have done that because shoals have a habit of moving during the season – sometimes past the buoys that mark them.

Close to the Shoals. In some cases, the routes passed close to shoals where there was no marker buoy such as Pickles Reef. The plotted route passed very close to these shoal patches, much too close for comfort as far as I was concerned.

To follow this route, you would be dependent on the accuracy of your GPS with no margins for error. Around Key Largo, the proposed route took a more inshore line between shoal patches and then towards Marathon the route took the buoyed channel west of Pigeon Key Banks before turning east towards the marinas at Marathon.

Miami to Nassau

Perhaps that was a tough route to ask the system to work on so the next one was to head from Miami across to Nassau in the Bahamas, the route followed by many boaters. This is a fairly straightforward route across the Florida Strait from Miami and then the Garmin took us around the northern end of North Bimini, following a track to pass north of the unmarked Moselle Bank rather than taking a more inside route to pass the marker on North Bank.

From there it was across the Flats to pass close the North West Shoal and then on the Nassau. In Nassau Harbor, the route skirted the cruise ship terminal and the shallow water to arrive at a marina. Apart from that channel north of North Bimini, this was a pretty safe route to follow as long as you had the GPS to ensure the safe passing of some of the shallows.

Summing up, you would need to do a lot of fine-tuning to make sure you had a viable route with the Garmin system, and you would need to check out the route in considerable details to ensure safe passing distances for many dangers.

Navionics

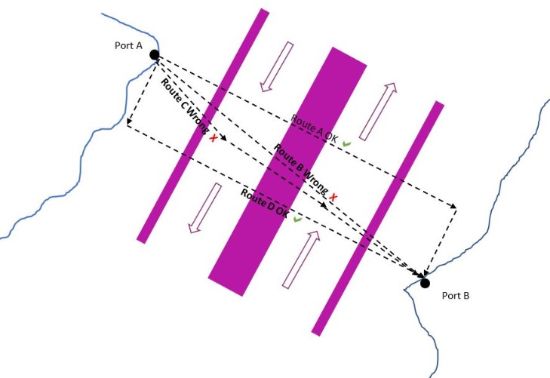

For the Navionics system we threw in some areas with traffic separation zones, which have strictly governed rules about what you should and should not do in these areas according to the COLREGS (international regulations for preventing collisions at sea). You are required to cross any of these traffic separation channels at right angles and if you are less than 20 meters (65.61’) in length you are best to try and keep out of them altogether.

Over that length and you have to use the channels but with no request for boat length, the Navionics system does not know how big you are. It ignores these traffic routes even though they are on the chart except to flag up a warning triangle to show you should be aware. To be fair, the Garmin system also ignores these traffic zones as well.

The Problem of Traffic Separation Zones

So, on a route from Seattle to Victoria on Vancouver Island which is littered with traffic separation zones, the system completely ignored them and took the straight line. The shortest routes across these busy waters could lead to some exciting encounters with big ships.

To be fair, the plotted route was littered with cautionary triangles, but I would have opted for a route inshore away from the big ships and only crossing the shipping lanes at right angles on a couple of occasions rather than zigzagging in and out of them. So, this route when plotted by auto-routing would have needed a lot of adjustment and quite frankly it would have probably been a lot easier just to start from scratch and plot the whole thing manually.

Montauk to Martha’s

On the east coast a route was plotted from Montauk to Sunset Lake on the northeast corner of Martha’s Vineyard. This route was plotted pretty well if you ignore the fact that once again the traffic separation zones heading into Rhode Island were ignored apart from the warning triangles. There was also one point where the route chose to pass inside a channel marker buoy with no gain in the distance covered. Although not relevant to this route the new wind farm to the south of Block Island was shown on the chart.

Observations

From these trials it does seem that auto-routing has a long way to go before it provides a trustworthy system of passage planning. On relatively simple routes where there are no or very few restrictions on where you can or cannot go such as along a straightforward coastline, it works reasonably well, but it is evident that the algorithm used is not geared to coping with traffic separation zones and has trouble handling challenging routes where there are options.

In fact, key features such as these zones seem to be completely ignored by both systems and unless you correct the course manually you could end up in court charged with an offense under the COLREGS by the Coast Guard if you followed the proposed courses implicitly. It is also evident that any proposed route relies heavily on having accurate GPS positioning because the clearance from dangers such as rocks and shallows can be quite small, too small for my comfort as a navigator.

That route down the Keys passed much too close to dangers for my liking. I plotted one route in European waters that took me right across a shoal area where the chart did show enough water, but that shoal was noted for its constantly changing shifting sands. Because auto-routing does not take into account the rise and fall of the tide it may persuade you that some of the useable short cuts are not available, when they can be safe to use when the tide is high.

Both systems will offer you a route in and out of harbor right into your marina berth but why you should need auto-routing in buoyed channels I am not sure. In buoyed channels, it is pretty clear where you need to be, and auto-routing does not keep you to the starboard side of the channel where you should be. In the open seas, auto-routing might have some merit by offering a basic route from which to start planning around.

Keep Checking. The display makes it quite clear that the proposed routes from auto-routing are not to be used for navigation without detailed checking -- but who reads the small print? It can be so easy to have a route plotted for you by auto-routing and then follow it implicitly just as you might do with your road system.

My advice is that auto-routing might be a guide to possibilities when you are at the planning stage of a cruise but when actually plotting the course stick to the tried and tested method of plotting it step by step and then checking it and checking it again.